Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

The effects of universal childcare policies in Spain during the 1990s. The policies led to a significant increase in public childcare enrollment, particularly among disadvantaged children, and had positive impacts on children's skills. However, the costs of private childcare remained high. The document also explores the potential long-term effects of universal childcare on children's cognitive and non-cognitive development.

What you will learn

Typology: Study notes

1 / 122

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

Department of Applied Economics PhD Program in Research of Applied Economics

Over the past few decades both developed and developing countries have made substantial progress in closing the gender gap in opportunities. However, even in developed countries, there are still significant gaps in the job opportunities for women and also in the wages paid to them compared with their male counterparts. In particular, although the employment of women has increased substantially, labor participation rates of mothers with small children is still very low in a substantial number of countries. In addition, although the share of women among college graduated has equaled or even surpassed the share of men, women are still underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) careers, in which workers earn considerably more than their non-STEM counterparts. The main aim of this dissertation is to provide new evidence that help us to improve our understanding of these two relevant topics on gender equality issues. In addition, policies aims to narrow the gender gap in opportunities also have unintended effects on other relevant fields. For instance, the provision of free childcare aims to allow the primary caregiver (usually the mother) the access to the labor market is debated because of the effect it may has on children' development. In that sense, this dissertation adopts a more comprehensive view of such a policy and also analyzes its consequences on children' cognitive outcomes. Doing this, it also provides evidence about a topic of high interest in education issues. In fact, the effects of universal provision of preschool on children' development have been a matter of growing attention in the last years with the recent contributions of Heckman and colleagues in the human capital theories that make a strong case for early investment in education. The dissertation consists of three essays with a marked empirical orientation. The first two essays provide empirical evidence about the effect of universal preschool provision on both maternal employment (first essay) and children' cognitive outcomes (second essay). The empirical questions to be answered by these essays are: 1) To what extend the universal provision of free childcare increases the labor participation of women with small children? 2) What happens to children's long-run cognitive development when introducing universal childcare mainly crowds out maternal care? Recent studies using quasi-experimental methods focus mostly on countries with already high female labor force participation rates, high childcare coverage rates, or with many

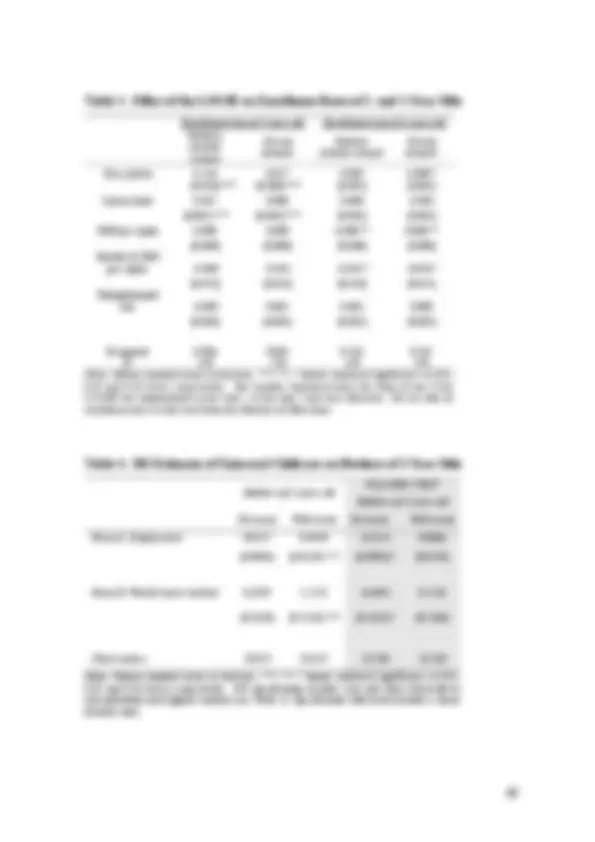

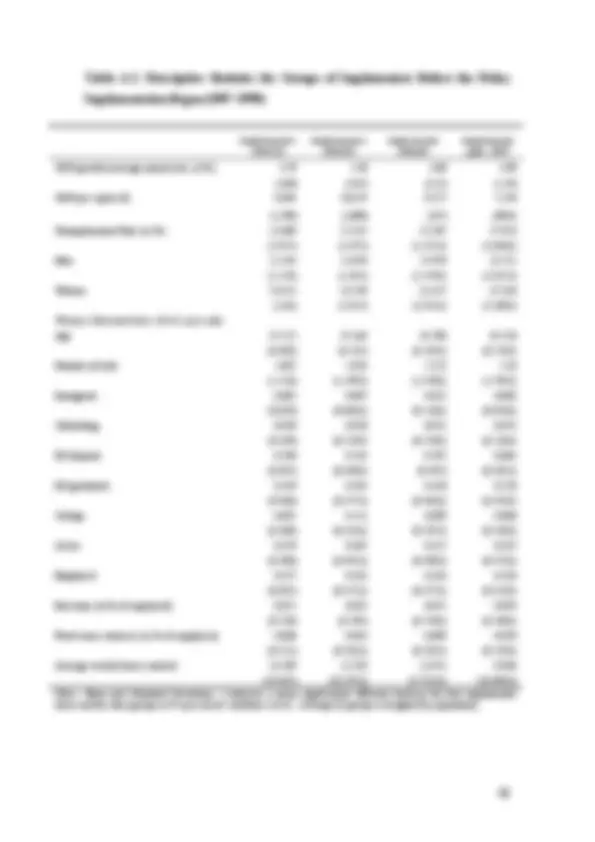

family-friendly policies. In such a context, the introduction of public childcare crowds out informal or private care arrangements. As consequence, they find modest effects on maternal employment and positive effects on children's skills, particularly among disadvantaged children. In contrast few studies analyze the effects of an expansion of full-time high-quality public childcare in a context of low female labor force participation and insufficient childcare supply, in which the policy mainly crowds out maternal care. Understanding the effects of introducing universal childcare in such a setting is the main contribution of the first two essays of this PhD thesis. To this, we use a quasi- experimental framework that arise from an educational reform carried out in Spain during the 1990s, which expanded the pre-school education to 3 years old. The third essay provides empirical evidence about the role of culture in explaining the gender educational gaps. There is an extensive literature documenting gender differences in the performance on different educational domains, from which arise the following stylized fact: whereas girls perform slightly better than boys at school at younger ages in most subjects, they start to diverge when they become teenagers, with boys performing better in math, and girls performing better in readings. These gender differences in educational achievement are likely to affect the choice of professional careers, and therefore they may to explain the persistence of gender inequality at older ages. Contributing to understand the sources of such gender differences in tests performance is the aim of the third essay of this dissertation. The question to be answered is: To what extend culture matters to explain gender differences in educational attainment? Recently, some researchers have found a correlation between the cross- country differences in the gender gap in mathematics and reading scores and several measures of gender inequality. They interpret this evidence as suggestive that the underperformance of girls in math relative to boys is eliminated in more gender-equal cultures. However, the interrelationship between institutions and norms makes it difficult to rigorously disentangle the two on this way. Moreover, since the effect is likely to work both ways, they do not capture a causal relationship. Does more gender equality lead to smaller intra-gender performance difference? Or is it smaller girls’ underperformance in math relative to boys where the society becomes more gender equal? This essay advances in these two fronts by examining second-generation immigrants in a host country to investigate whether culture determines behavior. This empirical strategy, known as "epidemiological" approach, exploits the fact that immigrants' children have lived under the institutions and markets of the host country but

2.1 Introduction

Earlier studies have found that maternal employment is very elastic with respect to price of childcare (with elasticities of around -1). However, recent studies using quasi- experimental methods suggest that these earlier estimates may have been overstated due to misspecifications of functional forms and violations of the exclusion restrictions. These studies uniformly find much smaller effects of public childcare on maternal employment as the introduction of public childcare crowds out informal or private care arrangements. Nonetheless, they focus mostly on countries with already high female labor force participation rates (such as the US, Canada, Israel, Sweden, and France), high childcare coverage rates (such as Argentina, Germany, and the US), or with many family- friendly policies (Sweden and Norway).^2 In contrast few studies analyze the effects of an expansion of full-time public childcare on maternal employment in a context of low female labor force participation and insufficient childcare supply. 3 The latter scenario, however, includes but is not restrictive to Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Spain, Switzerland, and Turkey in the OECD alone. Understanding the effects of introducing full-time universal childcare in such a setting is the main objective of this paper. We argue that understanding the effects of such reform on maternal employment is highly policy relevant in countries with low female participation as the difficulties to reconcile motherhood and work are among the explanations offered to explain the low levels of female presence in the labor force (Feyrer et al. 2008, and De Laat and Sevilla-Sanz 2011). Moreover, this study is

(^1) A different version of this essay was published as a discussion paper. Reference: Nollenberger, N. and Rodríguez-Planas, N (2011) "Child Care, Maternal Employment and Persistence: A Natural Experiment from Spain". IZA DP 5888. 2 Gelbach (2002), Schlosser (2006), Lefebvre and Merrigan (2008), Baker et al. (2008), Lundin et al. (2008), Goux and Maurin (2010), and Fitzpatrick (2010), analyze such type of reform in countries where the 25- to 54-year old female labor participation ranges between 67 and 85 percent. And Gelbach (2002) Berlinski and Galiani (2007), Lefebvre and Merrigan (2008), Baker et al. (2008), Lundin et al. (2008), Goux and Maurin (2010), Cascio (2009a), Fitzpatrick (2010), and Bauernschuster and Schlotter (2012), analyze the effects of public childcare expansion in a context in which childcare enrollment prior to the reform was between 40 and 80 percent. 3 To the best of our knowledge the only paper to do this is that of Havenss and Mogstad (2011a), which analyzes a 1970s staged expansion of subsidized childcare in Norway when the maternal employment rate was about 30 percent and subsidized child coverage below 10 percent. These authors find hardly any causal effect of subsidized childcare on the employment rate of married mothers because public childcare crowded out informal care.

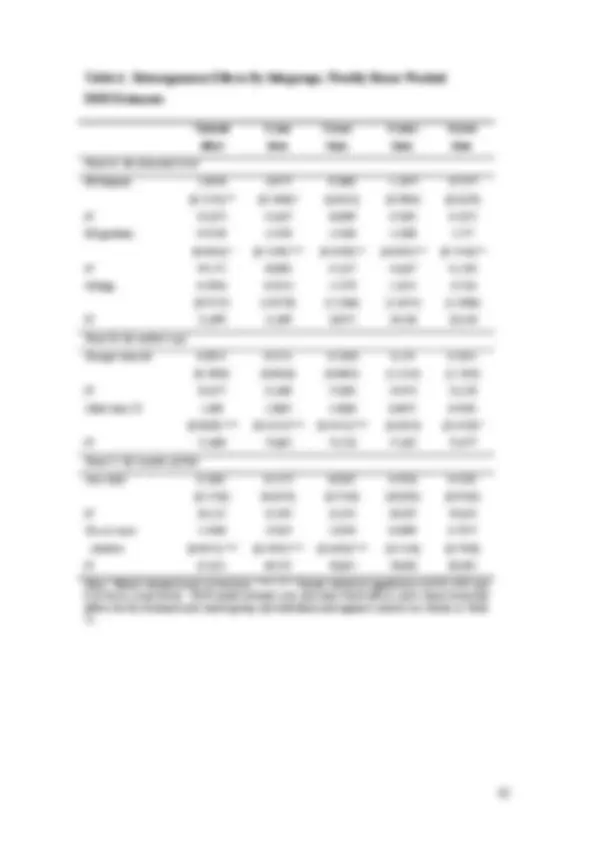

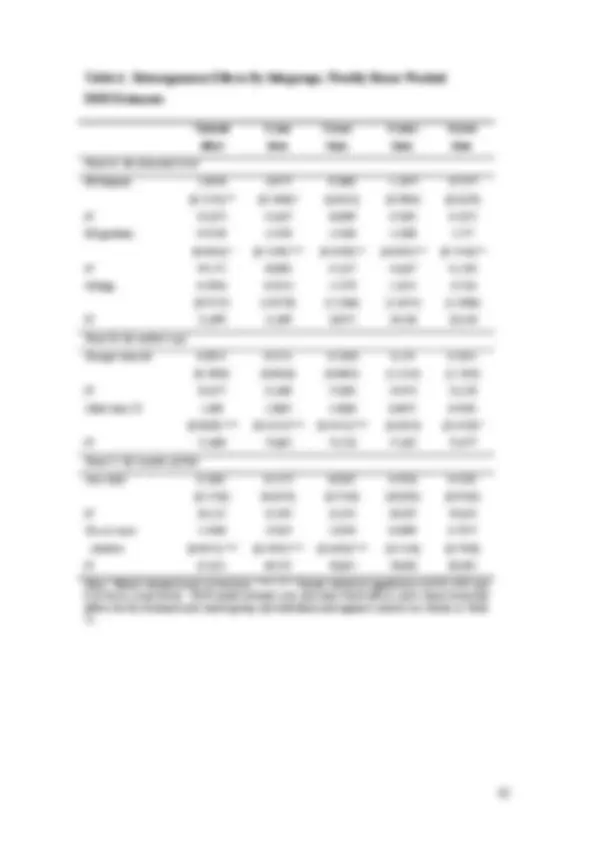

particularly relevant for countries, in which female labor force participation is relatively low (Boeri et al. 2005), access to proper childcare provisions is limited (Del Boca, 2002), and traditional family roles are deeply rooted (Bettio and Villa 1998; Sevilla-Sanz et al. 2010). We focus on an early 1990s reform in Spain, which led to a sizeable expansion of publicly subsidized full-time childcare for 3-year olds. Following the reform, overall enrollment rate in public childcare among 3-year olds increased from 8.5 percent in 1990 to 42.9 percent in 1997 and to 67.1 percent in 2002. Although the reform was national, the responsibility of implementing its preschool component was transferred to the states. The timing of such implementation expanded over ten years and varied considerably across states. Our analysis exploits this variation across time and states to isolate the reform's impact on the employment decisions of mothers of age-eligible (3-year-old) children. As the Differences-in-Differences (DD) approach may be biased if shocks specific to the treatment areas coincide with the policy changes (such as changes in state labor-market conditions), we apply a Differences-in-Differences-in-Differences (DDD) approach that exploits that the supply shocks to formal public childcare began at different points in time across different states and affected 3-year olds but not 2-year olds. We measure the effect of universal childcare for 3-year olds on maternal employment both at the time the child was eligible and as the child aged (up until the child is 7 years old). By shortening the time mothers spend outside the labor force, universal childcare can reduce mothers' human capital depreciation and preserve their job-search skills (as well as their social and professional networks), implying higher expected wages. Thus, women who would have chosen to stay out of the labor force in the absence of the policy, may decide to enter employment. If this is the case, the effects of this policy ought to persist as the youngest child ages. This may be particularly relevant in a context of low female labor force participation.4, 5 The analysis uses cross-sectional data from the 1987 to 1997 Spanish Labor Force Survey. The reason for focusing on the pre-1998 period is that the Spanish Government

(^4) To the best of our knowledge, the only other paper to examine persistence is that of Lefebvre et al., 2009, who analyze the effect of Québec’s universal childcare policy during a period of economic expansion and with 53 percent maternal employment rate. 5 When measuring the effects of this reform on maternal employment when the youngest child is 4- to 7- years old, we continue to use mothers of 2-year olds as a comparison group since these children are not affected by the reform. Thus, when estimating the effect one year later we compare mothers whose youngest child is 4 years old with mothers whose youngest child is 2 years old in the same quarter. Whereas children of 2 years old are never affected, when we observe children of 4 years old one year after the LOGSE was implemented in each state, they were affected when they were 3 years old.

Sections 2.6 and 2.7 present the results and several specification checks. Section 2. concludes.

2.2 Literature on childcare costs and female labor force participation

Although the theoretical implications of child-care costs on childbearing and work decisions may seem straightforward, Blau and Robins (1989) point out that the implications derived from even a simple economic model of simultaneous decision- making are actually quite complicated. A decrease in child-care costs is expected to lead to an increase in desired fertility due to a standard price effect. Similarly, cheaper child- care services would increase desired labor supply due to a lower opportunity cost of market work. However, the baseline time costs associated with childbearing might offset the increase in desired labor supply, effectively reducing labor force participation. It is also possible that the increase in desired labor supply is sufficient to induce a lower likelihood of childbearing. Thus, the net effects on fertility and labor force participation are ambiguous. However, a common effect is a reduction in role incompatibility: the decrease in the cost of child-care should reduce the likelihood and duration of labor force exit among women who bear children and should increase the likelihood of fertility among women in the workforce. More succinctly: there should unambiguously be an increase in the joint likelihood of work and fertility. Blau and Robins (1989) represent essentially the only other work that looks at the effects of child-care costs on simultaneous employment and fertility decisions. The analysis is conditional on initial employment status and uses geographic variation in average per-child weekly expenditures as the main measure of child-care costs. Blau and Robins find that higher local child-care expenditures are associated with lower rates of employment among all women and with decreases in childbearing among the non- employed. However, their measure of child-care costs is potentially endogenous as higher local expenditures might be the product of a greater local demand for child-care due to preferences or unobserved labor market conditions. There is a substantial number of studies that show that young children have a strong negative impact on their mother's labor supply. Heckman (1974) was among the first ones to show that an increase in childcare costs reduces the mother's labor supply and the number of hours worked (conditional on employment). However, examining the U.S. empirical literature, Anderson and Levine (2000) and Blau and Currie (2006), report

that estimates for the elasticity of employment with respect to the price of childcare range from 0 to values greater than -1, and that this discrepancy between the estimates can be explained by differences in the population studies, the data sources used, the model specification and the econometric methodology. In Canada, the estimates range from - 0.156 to -0.388, indicating a more modest response (Cleveland et al. 1996; Powell 1997; and Michalopoulos and Robins 2000). Traditionally, most studies have used non-experimental data, and various bias correction methods to address the two key selection problems in this literature: the female labor supply participation, and, given labor supply participation, the use of formal child- care as opposed to informal or relative care. One common approach has been to estimate the effects of child-care costs on women labor supply with a sample of mothers who were employed and who paid for childcare, applying corrections for selectivity (see, for instance, Connelly 1992; Kimmel 1995; and Ribar 1992). Alternatively, others have used structural models to identify the effects of child-care costs on female labor supply (Michalopoulous et al. 1992, and Ribar 1995). Finally, others have exploited geographic variation in child-care costs or nonlinearities of child-care tax credit for the identification (see Blau and Robins 1989, for the former approach; and Averett et al. 1997, for the latter approach). An alternative approach has been to use an experimental or quasi-experimental approach to identify the effect of child-care costs on mothers labor supply. Gennetian et al. (2001), provide a good review of several recent demonstration programs for low- income families that randomly offered childcare subsidies to welfare recipients. Unfortunately, because these programs typically offered other services in addition to child-care subsidies, it is difficult to isolate the effect of child-care on labor force participation per se. In contrast, the quasi-experimental approach has been a good way to identify the problem at hand. Berger and Black (1992), were amongst the first to use this approach by comparing women receiving subsidized childcare to otherwise similar women who are on a waiting list for this care. Their estimates indicate that elasticity of employment with respect to subsidy rates ranges from 0.094 to 0.35. Alternatively, Gelbach (2002), uses the quarter of birth of the child as an instrument for public school enrollment of five-year-old children. He finds that that access to free public school increases the employment probability of (single and married) mothers whose youngest child is aged five, with an implied elasticity of labor supply with respect to childcare costs of –0.13 to –0.36.

2.3 Overview of the Spanish Public Childcare System

School and Preschool Prior to the Reform Mandatory schooling in Spain begins at age 6. However, preschool for 4- and 5-year olds is also offered in the premises of primary schools from 9 am to 5 pm (regardless of school ownership status). Once a primary school offers places for 4-year olds, parents who wish to enroll their children to that particular school will do so when the child turns 4 years old as the chance of being accepted in the school may decrease considerably a year later (because priority of enrollment of 5- or 6-year olds is given to those children already enrolled in that particular school when they were 4 years old). As a consequence, enrollment rates for 4- and 5-year olds in the late 1980s were 94 and 100 percent, respectively. Primary and secondary schooling is either public or private.^6 Public schools are free of charge, except for school lunch, which costs about 100 € per child per month. Private school costs are higher - between 250 and 350 € per child per month (including lunch).^7 At the beginning of the 1990s, childcare for children 0- to 3-years old was rather scarce, predominantly private, and also quite expensive (on average it costs between 300 and 400 € per child per month--including lunch). In contrast with Scandinavian countries and the US or Canada, family day care, in which a reduced number of children are under the care of a certified carer in her house, is practically non-existent. In Spain, children under 4 are either in formal (public or private) childcare or with their mother (or grand- mother). Unfortunately, information on grand-mother's care is unavailable. As a consequence, this paper considers motherly care as equivalent to care provided by the nuclear family.

The Reform In 1990, Spain underwent a major national education reform (named LOGSE) that affected preschool, primary and secondary school.^8 The focus of our study lies on the preschool component of this reform, which consisted of a regulation of the supply and the quality of preschool, and its implementation began in the school year 1991/92. The

(^6) About one third of children in primary school in Spain are enrolled in private schools. (^7) In this paper, private schools refer to "escuelas concertadas" for which the government subsidizes the staff costs (including teachers). There are a very small number of private schools, which tend to be foreign schools (such as the French, Swiss or American schools), and cost two to three times more than the average "escuela concertada". 8 The primary and middle school component of the reform was first introduced in the school year 1997, which is basically outside of our period of analysis, consequently having no potential impact on our results.

LOGSE divided preschool in two levels: the first level included children up to 3 years old, and the second level included children 3 to 5 years old. While not introducing mandatory attendance, the government began regulating the supply of places for the 3 year olds. Prior to the LOGSE, free universal preschool education had only been offered to children 4 to 5 years old in Spain. After the LOGSE, preschool places for 3 year olds were offered within the premises of primary schools and were run by the same team of teachers. This implied that childcare for 3 year olds operated full-day (9 am to 5 pm) during the five working days and followed a homogeneous and well thought program. With the introduction of the LOGSE schools also had to accept children in September of the year the child turned 3 whenever parents asked for admission if places were available. Available preschool places were allocated to those who had requested admission by lottery (regardless of parents’ employment, marital status, or income). As explained earlier, although enrollment was not mandatory, it was necessary to ensure a place in the parents' preferred school choice. As a consequence, child-care enrollment among 3- years-old children went from meager to universal in a matter of a decade. 9 Between the academic years 1990/91 and 1997/98 the number of 3-years-old children enrolled in public preschool centers quintupled from 33,128 to 154,063.^10 Federal funding for preschool and primary education increased from an average expenditure of € 1,769 per child in 1990/91 to €2,405 in 1996/97 (both measured in 1997 constant euros), implying a 35.9 percent increase in education expenditures per child.^11 Besides regulating the supply of public child-care, the LOGSE also provided for the first time in Spain federal provisions on educational content, group size, and staff skill composition regardless of ownership status for children 3 to 5 years old. Psycho- educational theories such as constructivism (put forward by Jean Piaget, and Lev Vygotsky) and progressive education (based on Célestin Freinet and Ovide Decroly) served as a guideline for the design of the curriculum. There was a strong emphasis on play-based education, group play, learning through experiencing the environment, problem solving and critical thinking (LOGSE; 3 rd^ October 1990). While the pedagogical movements behind the LOGSE are close to those in Scandinavian countries, they have

(^9) Unfortunately we only have information on enrollment rates and not on actual supply rates for 3-year olds. In the context of rationed supply, enrollment rates should, however, resemble coverage rates quite closely. 10 These figures exclude Basque Country, Navarra and Ceuta and Melilla as they are not included in our analysis. 11 Unfortunately data disaggregated at the preschool level is not available.

childcare for 3-year olds did not crowd out private enrollment (also shown in Figure A.1). Following Havnes and Mogstad (2011a), we focus our analysis on this early expansion. The reason is that the early expansion is more likely to reflect the sudden increase in public preschool places for 3-year olds than an increase in the regional demand for daycare. In Sections 2.5 and 2.6, we discuss potential endogeneity of the reform and the timing of the implementation of the legislation across states.

2.4 Empirical Strategy

Current effect of the reform Most of the studies using the natural experiment framework apply the Differences-in- Differences (DD) approach, which (as explained by Cascio 2009a) may be biased if shocks specific to the treatment areas coincide with the policy changes (such as changes in state labor-market conditions) or if there are permanent unobserved differences between mothers residing in treatment and comparison areas. To address these concerns, we apply a Differences-in-Differences-in-Differences (DDD) approach that exploits that the supply shocks to public childcare began at different points in time across different states and affected 3-year olds but not 2-year olds. 13 Sensitivity analysis also presents estimates from a DD approach only using 3-year olds and exploiting regional variation across time. In addition, as one may be concerned that the reform may have also affected mothers of 2-year olds by changing the expected cost of work for these mothers when their child turns 3 years old, we also used a different control group, mothers whose children were up to two years older than our treatment group to avoid this potential "anticipation effect". Finally, using a DD approach we estimated whether there was an "anticipation effect" of the reform on mothers of 2-year olds and did not find any evidence of it in the short- or medium-run. Our basic DDD model, estimated by OLS over the sample of mothers whose youngest child is 2 and 3 years old, can be expressed as: 14

Y (^) it =α 0 + α 1 Post_reformt + α 2 Treatedi + α 3 (Post_reform (^) _t *Treatedi )+

(^13) Public and private enrollment for 2 year olds over the period remained well below 7 percent over the period. 14 We use linear probability models in all specifications. However, we replicated our analysis using logit models and find very similar results.

where Y (^) it is the employment outcome of interest for woman i in quarter t. We present estimates of employment at survey date and weekly hours worked. Post_reform (^) t takes value of 1 if the period is after the beginning of implementation of the reform in each state, and 0 otherwise. We follow the classification of states presented in Table A.1. For instance, in Madrid Post_reform (^) t takes value of 1 beginning in the fourth quarter of 1992 and forward, and 0 otherwise. Treatedi takes value of 1 if the mother’s youngest child is 3-years old, and 0 if her youngest child is 2-years old. We used the year of birth of the child (instead of the child’s age reported at the time of the survey) to define the treatment group. The reason for this is that the Spanish enrollment rule is such that, in order to begin the academic year t/(t+1) , which starts each September, the child must have turned the mandatory age (3 years in this case) on or prior to December 31st^ of the calendar year t. Since the Spanish LFS is a quarterly cross-sectional dataset, this implies that our “treatment” group is defined as mothers whose youngest child is 3-years old during calendar year t-1 for LFS quarters one through three of year t , and as mothers whose youngest child is 3-years old during calendar year t for the fourth quarter of year t. Following the same rule, we define mothers whose youngest child is 2-years old as those whose youngest child has turned 2 in the previous (current) calendar year if we observe them in quarters one through three (four). Moreover, we eliminate from our “control” sample mothers who had a 3-year old (in addition to a 2-year old). The reason for this is that these mothers are eligible to benefit from the universal childcare by enrolling their 3- year olds and this may affect their employment decisions. This implies losing 2, observations (less than 2 percent of our sample). However, results are robust to relaxing this restriction. The vector Xit includes individual-level variables expected to be correlated with employment: age, age squared, dummies indicating the number of other children, a dummy for being foreign-born, educational attainment dummies (high-school dropout, high-school graduate, and college), a dummy for being married or cohabitating. In addition, we include state level unemployment rate to control for possible differences across regional labor markets. We also include state and year fixed effects controlling for permanent differences in maternal employment across states and for the general Spanish economy business cycle, respectively. In addition, to control for possible pre-period trends that could bias the results (Meyer 1995), we also include a quarterly linear time trend, t , which differs for the treatment and control group, so that we can control for

they affected mothers’ employment decision, our analysis focuses on the years 1987 to 1997 to avoid potential policy interactions. Furthermore, migration across states in Spain is surprisingly low (Jimeno and Bentolilla 1998, Bentolilla 2001). Thus, there is little concern that the policy may have induced families to move from slow implementing states to fast implementing states. Finally, in the specification tests section we evaluate whether endogeneity of fertility is a concern.

2.5 The Data and Descriptive Statistics

We use data from the second quarter of 1987 through the last quarter of 1997 of the Spanish Labor Force Survey (LFS). The reason for not using data prior to the second quarter of 1987 is that information on the year of birth of the children is not available. As explained earlier, we focus our analysis on the years prior to 1998 to minimize concerns regarding potential policy interactions. The Spanish LFS is a quarterly cross-sectional dataset gathering information on socio-demographic characteristics (such as, age, years of education, marital status, state of residence, marital status), employment (including weekly hours worked), and fertility (births, number of children living in the household, and their birth year). Unfortunately, we do not observe children’s day care enrollment precluding us from analyzing a “first- stage” model as in Cascio (2009a) and Berlinsky and Galiani (2007), with a dummy for public day care enrollment of the mother’s youngest child as dependent variable. We restrict our sample to mothers between 18 and 45 years old at survey date. Moreover, we exclude the Basque Country and Navarra from the analysis because of their greater fiscal and political autonomy since the mid-1970s, implying that their educational policy differed from that of Spain as a whole. The final sample size is of 105,748 observations. Unfortunately, the LFS has no information on wages. Optimally, we would have liked to use a recently available longitudinal dataset from Social Security records that contains information on wages, the Continuous Survey of Work Histories (CSWH). However, we decided against the longitudinal dataset for the following reason. The CSWH provides the complete labor market history for those women registered in the Social Security Administration in 2004. This implies that if a woman worked in the early 1990s and after having a child she decided to leave the labor force, she is not included in

the CSWH. As most of our analysis focuses on the early- and mid-1990s, and labor force participation among mothers of young children at that time was low (around 35 percent prior to the reform), we are concerned that the data from Social Security records will provide estimates of the reform biased towards those women who are strongly attached to the labor force. As we consider that the relevant question here is the employment decision, we prefer focusing on the LFS, which is a representative sample of the Spanish working-age population.

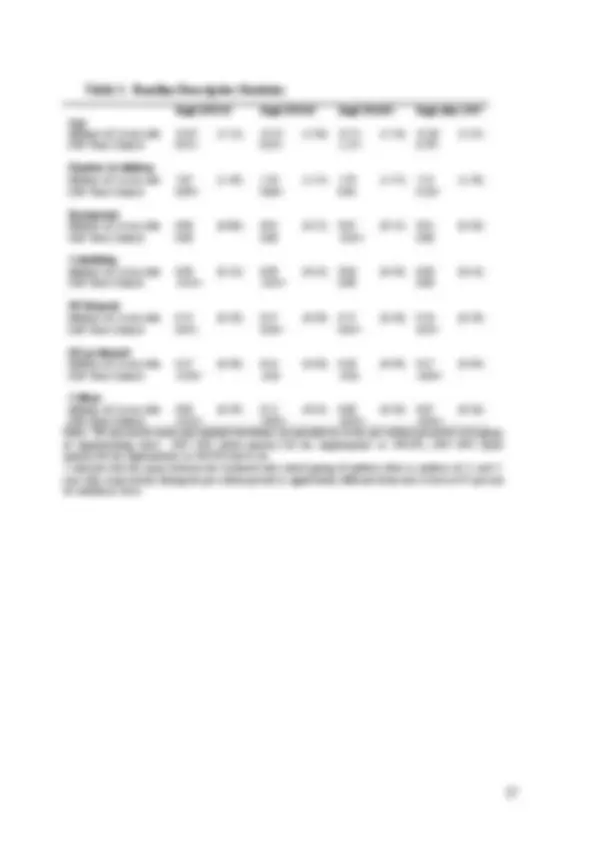

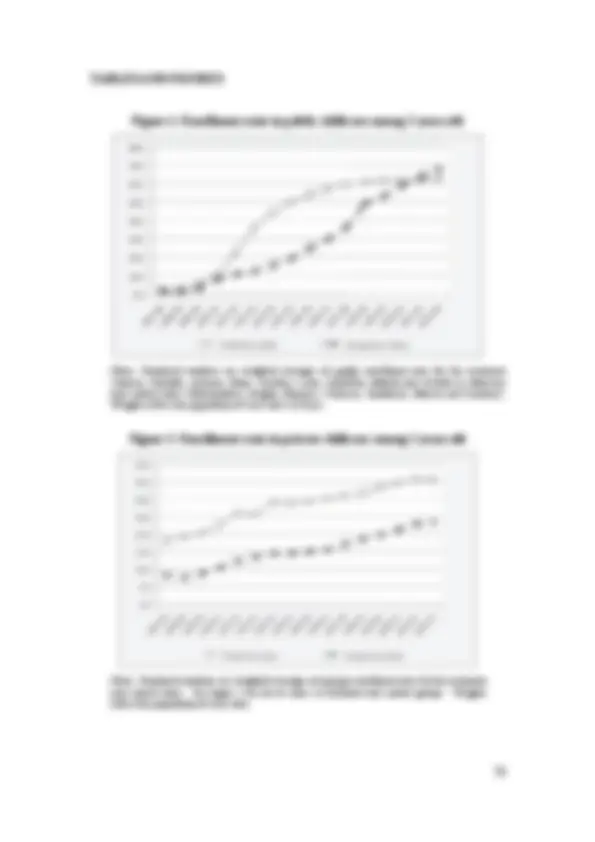

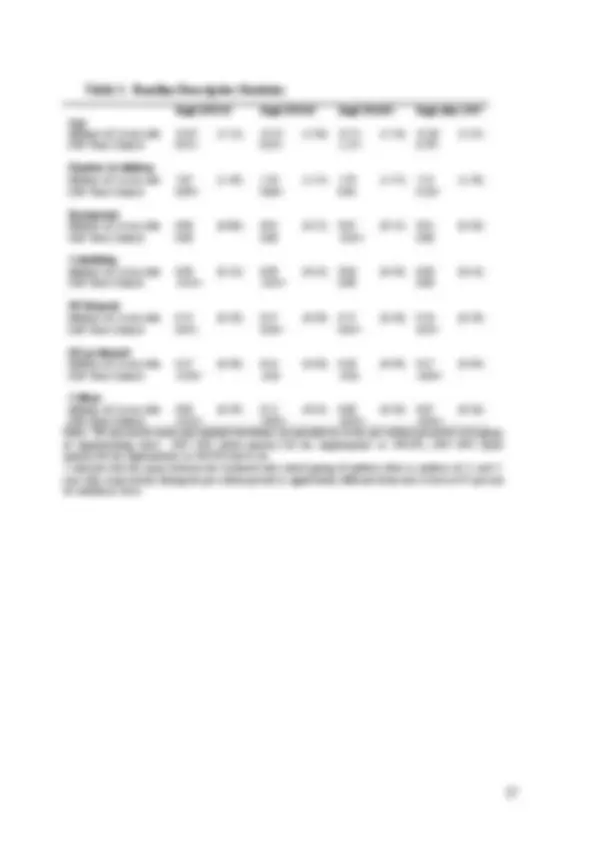

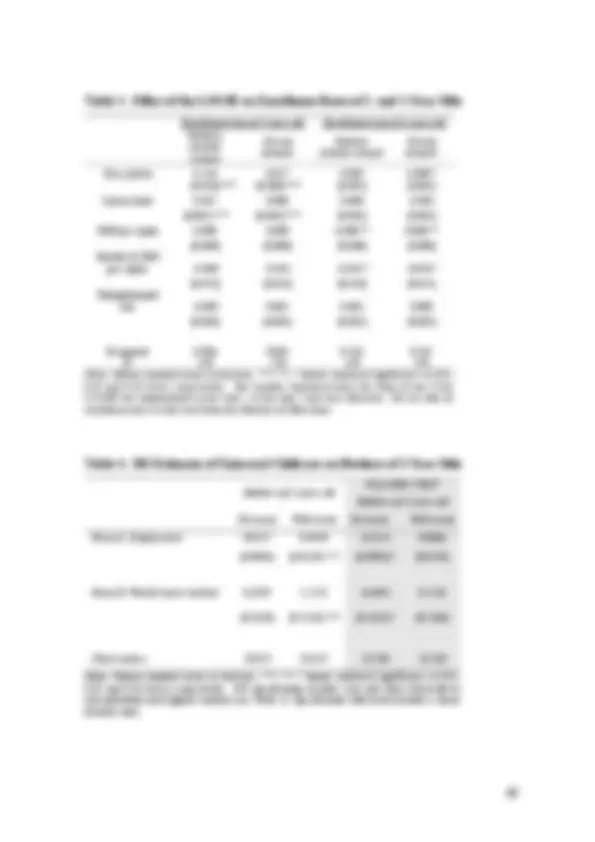

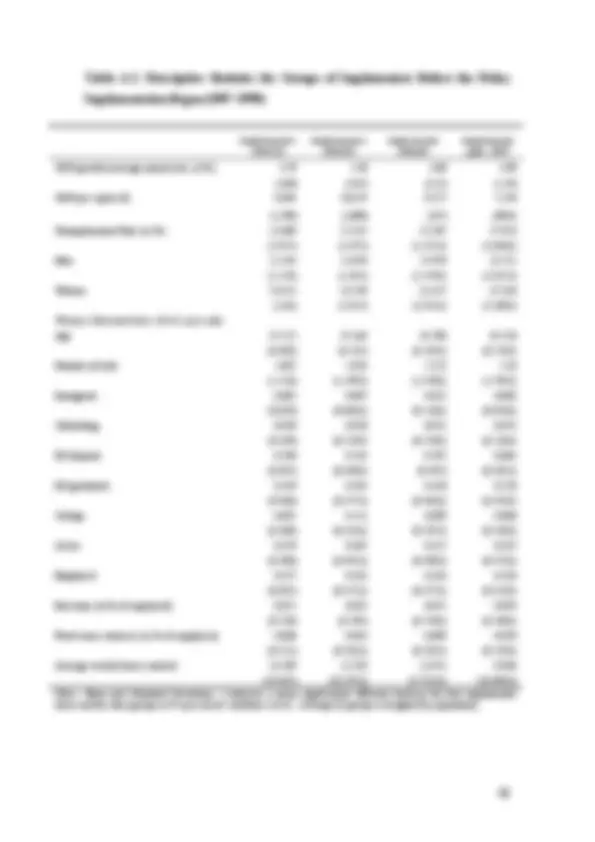

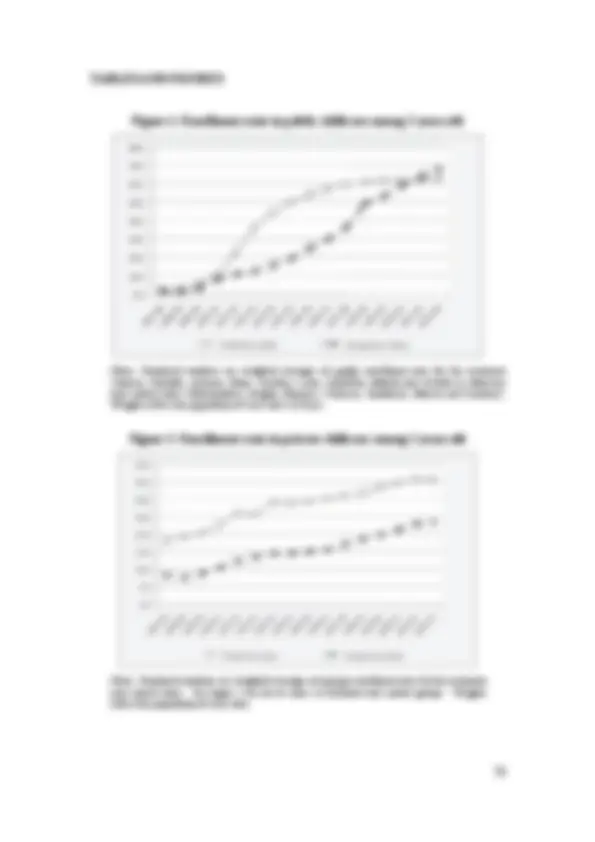

Descriptive Statistics Table 1 presents baseline summary statistics for the main variables that may affect employment decisions for the treated group for each group of implementing states. These pre-reform means are estimated during the years prior to the implementation of the reform in each of the states, as explained at the bottom of Table 1. In addition, Table 1 also presents treatment and control pre-reform baseline differences. Treated and control mothers are quite similar within and between each group of implementers. However, there are small but statistically significant differences: treated mothers are somewhat older, have a slightly higher number of children, are slightly less likely to be married or cohabitating, and are less educated than those whose youngest child is 2 years old. As explained earlier, our specifications control for these observable differences. One concern is the potential endogeneity of our policy. For example, we may worry that the increase in public preschool places for 3-years old in a particular state was a response to the increasing incidence of working mothers. We may also be concerned if short-term falls in employment immediately before 1990 triggered the reform. To address these concerns, Figure 2 shows maternal employment rates and weekly hours worked for mothers whose youngest child is 2, compared to those whose youngest child is 3. Each outcome series was calculated by setting t = 0 as the quarter in which implementation began in each state (for instance, fourth quarter of 1991 for Cataluña, fourth quarter of 1992 for Madrid, fourth quarter of 1994 for the Canary Islands, and so on), and estimating a weighted average across states at each point in time. Figure 2 shows that both the employment rate and weekly hours worked of all mothers with young children increased quite steadily in the quarters preceding the implementation of the reform. 16 The policy change may have been a response, at least in part, to (long-term)

(^16) The average hours worked is low because our sample includes both employed and not employed women.