Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

Pregnant teenagers face serious health, socio-economic and educational challenges. One teenage learner pregnant is one too many, and the Department therefore ...

Typology: Study notes

1 / 147

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

Produced by the Human Sciences Research Council on behalf of the Department of Basic Education, with support from UNICEF.

Suggested citation:

Panday, S., Makiwane, M., Ranchod, C., & Letsoalo, T. (2009). Teenage pregnancy in South Africa

- with a specific focus on school-going learners. Child, Youth, Family and Social Development, Human

Sciences Research Council. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education.

August 2009

ISBN No.: 978-0-620-44701-

Purpose

The purpose of the study was to document, review and critically analyse literature on teenage pregnancy with a focus on school-going adolescents. The specific objectives were as follows:

Methods

The study involved a desktop review of literature supported by secondary data analysis to provide an overview of research on the prevalence, determinants and interventions for teenage pregnancy.

Although the study focused on pregnancy, the detailed trends presented in the report are on fertility. Understanding the distinction between pregnancy and fertility is essential. Fertility rates refer only to pregnancies that have resulted in live births while pregnancy rates include both live births and pregnancies that have been terminated. Before the introduction of the termination of pregnancy legislation, fertility closely approximated pregnancy rates. Since the legalisation of abortion, however, this can no longer be assumed to be the case. Trends in pregnancy rates in SA cannot be accurately estimated for two reasons. First, it is not known whether pregnancies that were terminated early on are well captured in survey data and school record systems. Second, a comprehensive national register of abortion is not maintained in the country.

SA lacks vital statistics on fertility, pregnancy and abortion. Nevertheless, fertility rates could be reliably estimated from Census data and the Demographic and Health Surveys. For the purposes of this study, trends in teenage fertility were investigated in three stages: (1) mapping the overall trends in fertility in SA; (2) documenting trends in teenage fertility relative to overall fertility; and (3) analysing learner pregnancies reported through the Education Management Information System (EMIS).

The literature review focused on studies dated between 2000 and 2008 but included seminal works prior to

Secondary analysis was also conducted on the HSRC 2003 Status of Youth Survey, a nationally representative study of more than 3 500 young people aged between 18 and 35 years. The purpose of the secondary data analysis was to identify factors that are associated with early pregnancy. This included family structure, type of childhood residence, childhood poverty and school dropout.

Main Findings

Fertility

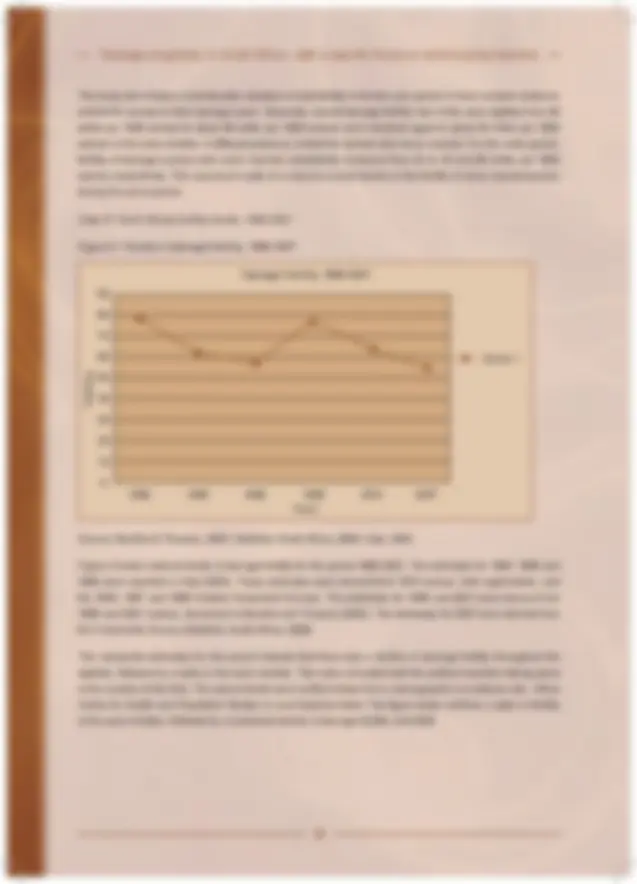

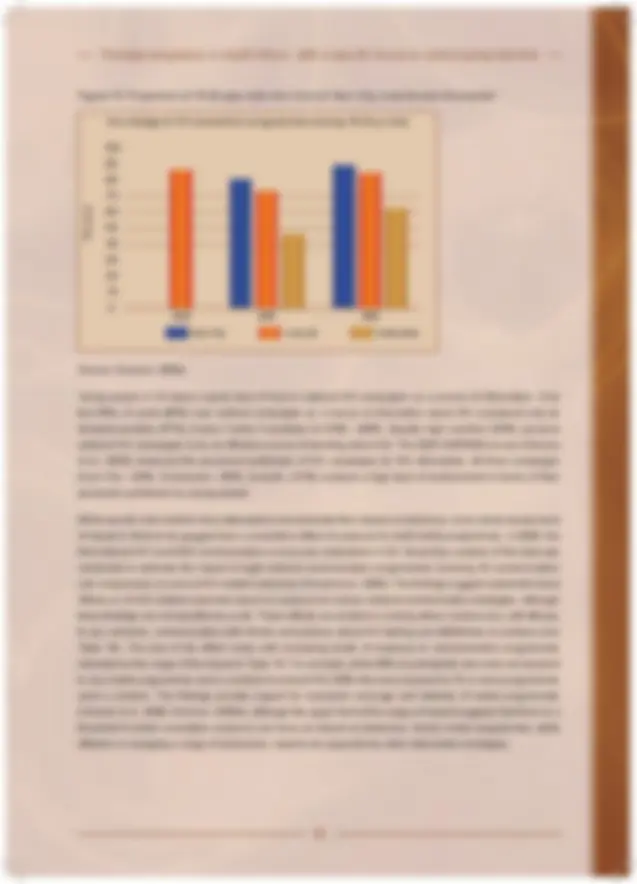

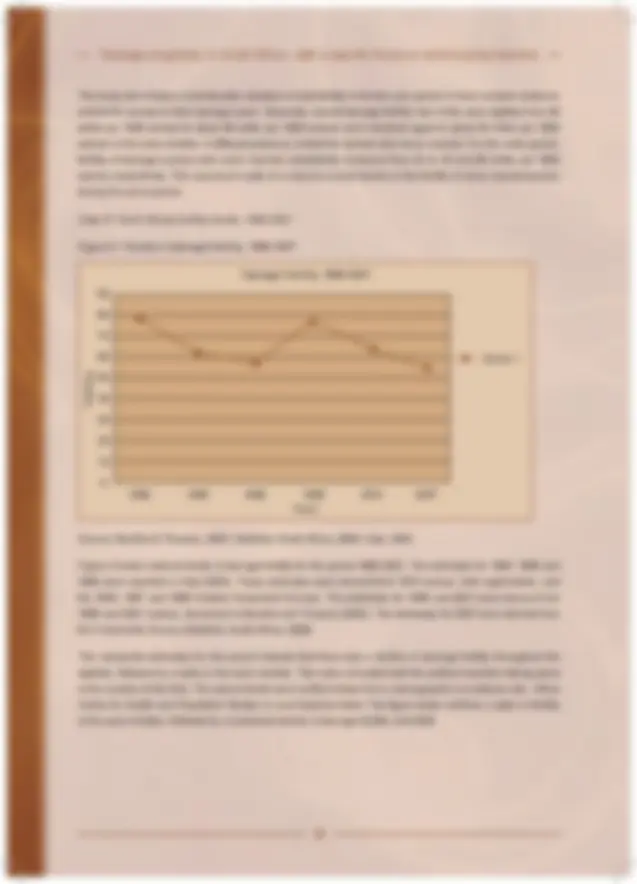

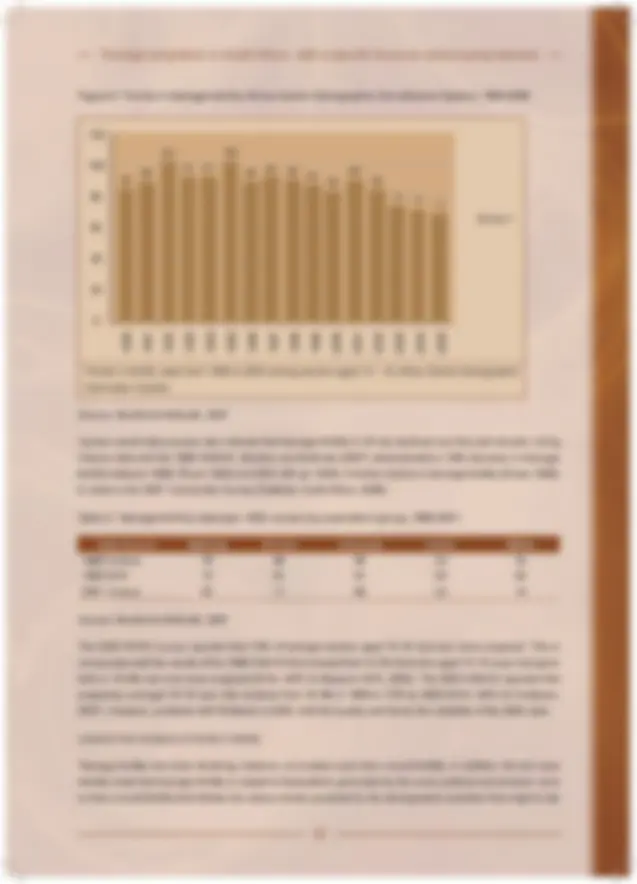

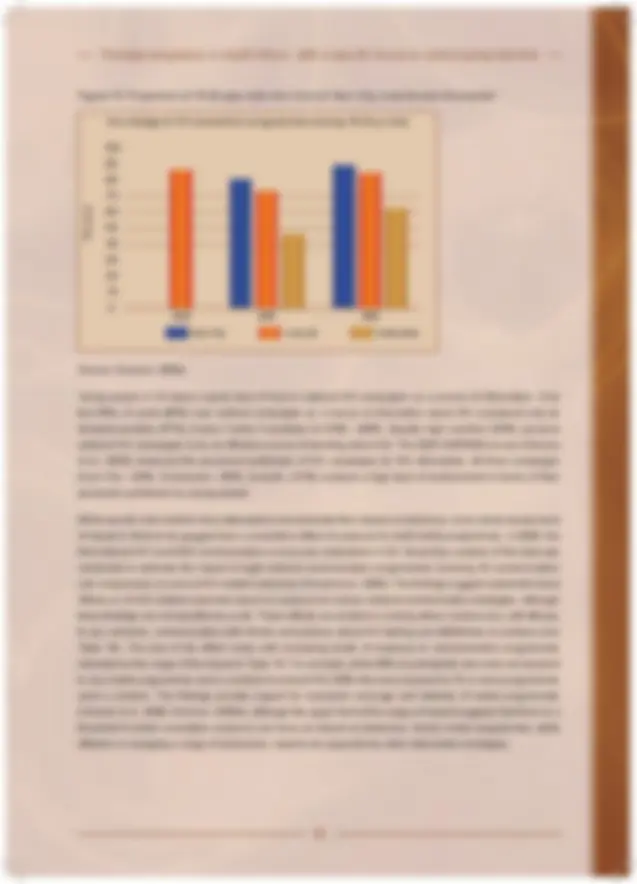

The overall decline in fertility in South Africa has run a long course of almost 50 years but at differential rates for the population groups. To date, SA has the lowest fertility rate in mainland sub-Saharan Africa. While over time teenage fertility has been declining, this has been at a slower pace than overall fertility. The slower decline in teenage fertility may be attributed to interruptions in fertility associated with national epochs. For example, the interruption of schooling during the struggle years was associated with a rise in teenage fertility. Similarly, the spike in fertility in the mid nineties is associated with political changes during that period when there were concerns for the large cohort of young people who had become marginalised from mainstream systems of education, work, healthcare and family life. However, it must be noted, that teenage fertility has declined by 10% between 1996 (78 per 1000) and 2001 (65 per 1000). A further decline in teenage fertility (54 per 1000) was reported in the 2007 Community Survey.

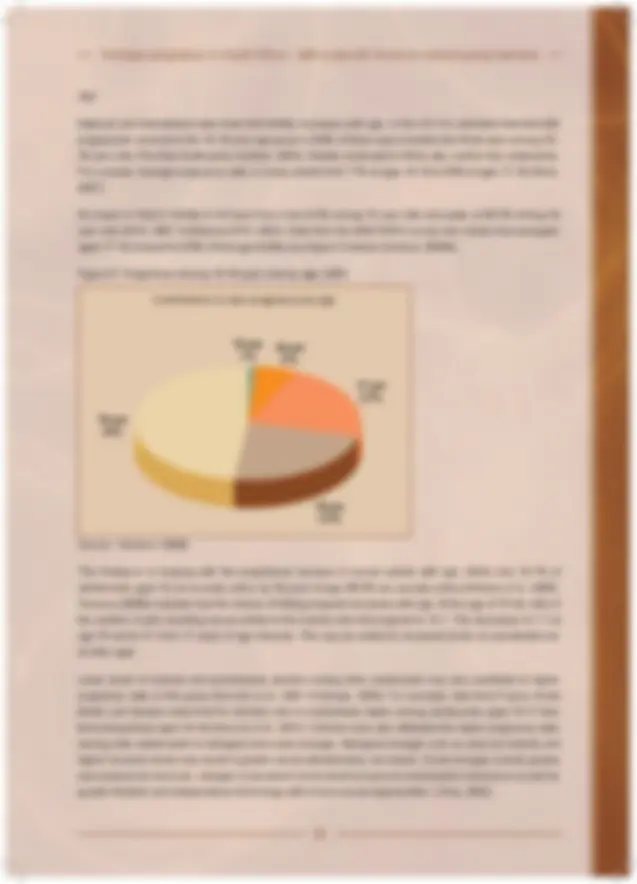

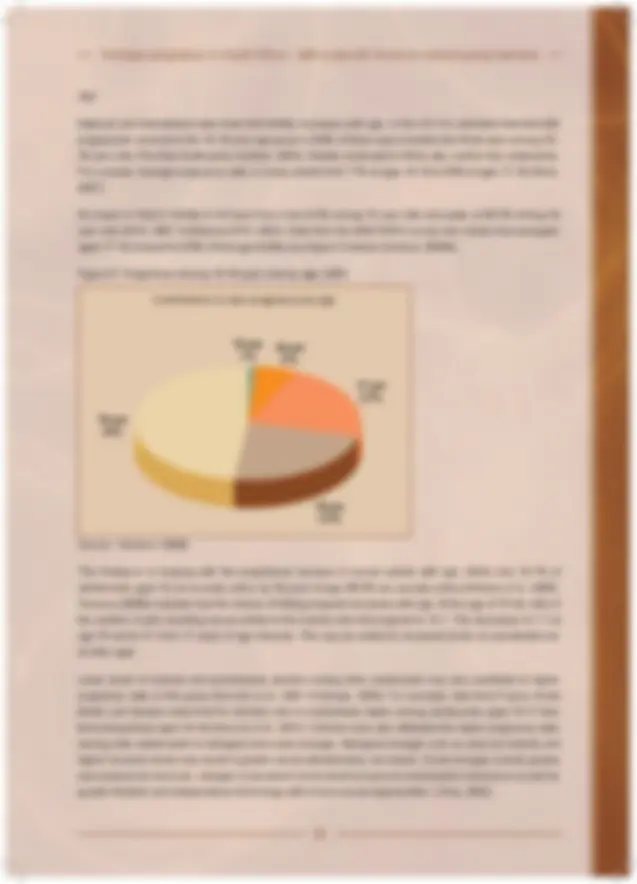

Older adolescents aged 17-19 account for the bulk of teenage fertility in SA. While rates are significantly higher among Black (71 per 1000) and Coloured (60 per 1000) adolescents, fertility among White (14 per

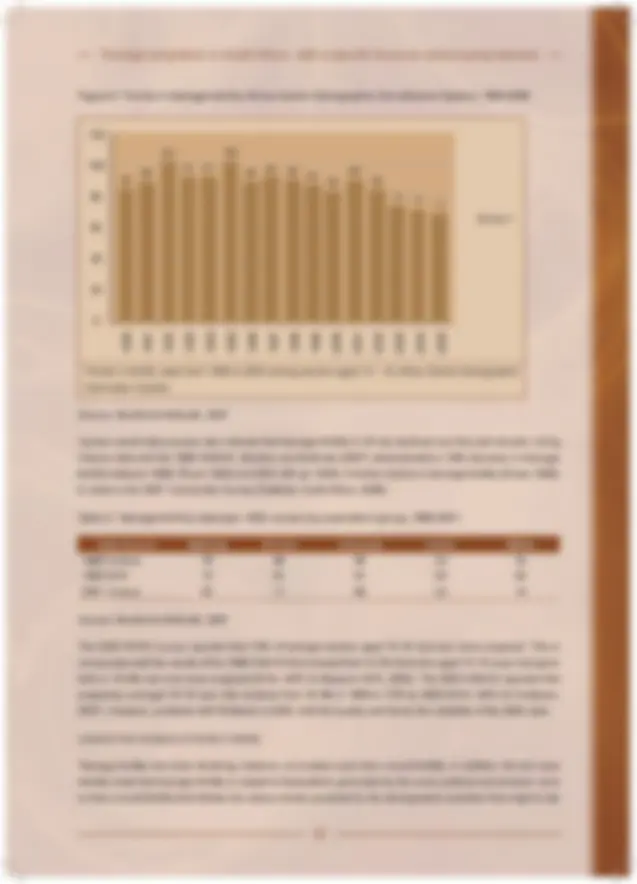

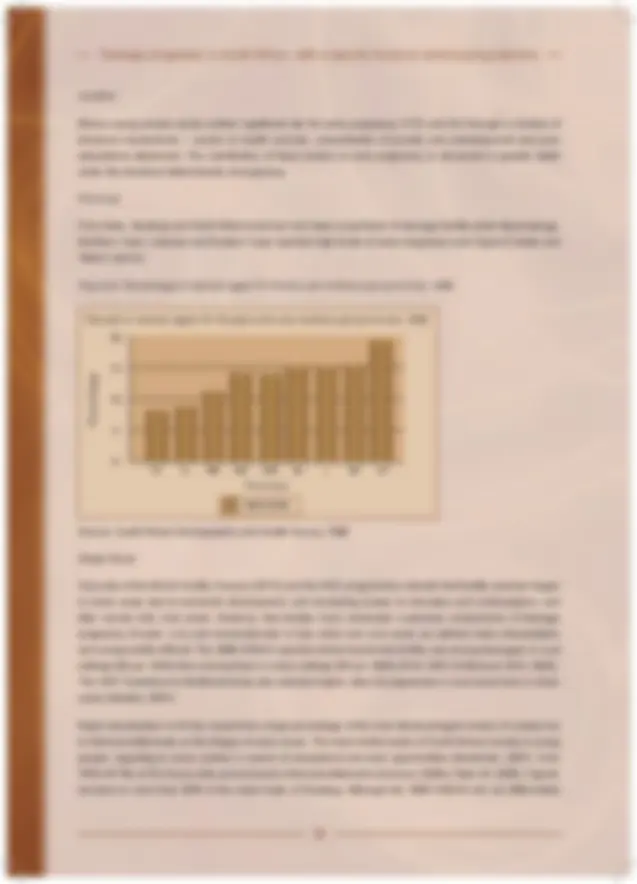

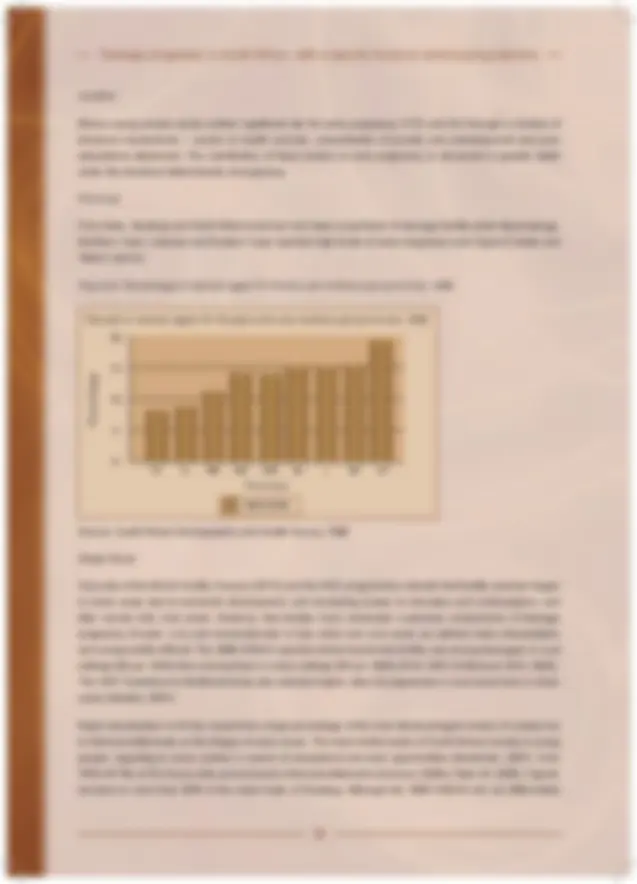

Analysis of the EMIS data on teenage pregnancy shows an increase in learner pregnancies between 2004 and 2008. However, this trend is contrary to national trends in fertility and is more likely the result of improved reporting, rather than a real increase in fertility. Analysis of provincial trends shows a concentration of learner pregnancies in the Eastern Cape, Kwazulu-Natal and Limpopo. Despite the incompleteness of the EMIS data, it does provide some indications of the types of schools in which learner pregnancies are concentrating. Learner pregnancies are higher in schools that are poorly resourced (lower in specialised schools), those located in poor neighbourhoods (no fee schools and schools located on land independently owned), as well as in schools that involve considerable age mixing (combined schools). Targeted interventions may be required for combined schools and those located in the poorest neighbourhoods.

Abortion

Despite the legalisation of abortion in SA in 1996 and the progressive increase of service availability in public and private facilities over time, few teenagers report using legal services for termination of pregnancy in both quantitative (3%) and qualitative data. Administrative data from the Department of Health, however, suggests much higher levels (30%) of usage of legal services by young women aged 15-19. These data sources need to be reconciled to establish a true estimate of use of services. Failure to use legal services is related to the ensuing lack of information about the costs of termination and the stage of gestation at which legal termination can take place, as well as the stigma of pregnancy and abortion generated in the community and replicated within the health system. Although abortion is recognised as morally and religiously objectionable, young people apply a ‘relative morality’ to abortion to circumvent both social and financial hardships and to protect their educational opportunities. So termination does take place, albeit, illegally.

of, or results from, dropout, local and international studies show that both share the common antecedent of poverty and poor school performance. While pregnancy may be the endpoint most directly associated with dropout, it is often not the cause. Girls who perform poorly at school are more likely to dropout of school, experience early fertility and less likely to return to school following a pregnancy. In fact data from SA shows that dropout often precedes pregnancy. Incomplete education has been identified as a significant risk factor for negative reproductive health outcomes, including early pregnancy and HIV.

Even when girls have experienced an early pregnancy, South Africa’s liberal policy that allows pregnant girls to remain in school and to return to school post-pregnancy, has protected teen mother’s educational attainment and helped delay second birth. However, only about a third of teenage mothers return to school. This may be related to uneven implementation of the school policy, poor academic performance prior to pregnancy, few child-caring alternatives in the home, poor support from families, peers and the school environment, and the social stigma of being a teenage mother. South African data shows that the likelihood of re-entering the education system decreases when childcare support is not available in the home and for every year that teen mothers remain outside of the education system.

Instituting strategies to retain girls in school by addressing both financial and school performance reasons, as well as ensuring early return post-pregnancy, may be the most effective social protection that the education system can offer to prevent and mitigate the impact of early pregnancy. When learners do dropout of school, concerted effort is required to re-enrol them in school or in alternative systems of education.

Young fathers

Despite the growing focus of research on fatherhood in SA, scant data is available, both locally and internationally, on young fatherhood. Available international research suggests that the profile of young fathers is no different from young women – they tend to come from low income homes, have poor school performance, low educational attainment and seldom have the financial resources to support the child and the mother. Our secondary analysis shows that premature exit from the schooling system almost doubles the odds of becoming a father early on in SA.

Qualitative research among young fathers in SA reports that much like young women, young men experience a strong emotional response on hearing about their impending fatherhood. Contrary to the perception of young women that many young fathers deny paternity, most young men in the study expressed a sense of responsibility for the child and a willingness to be actively involved in the child’s life, motivated by the absence of their own fathers in their lives. But the acknowledged caring role of a father is overtaken by a need to provide financially for the child. In a context of pervasive unemployment, few young men can fulfil this role often leading to estrangement from the child. In addition, poor relations between the female partner and her family, together with cultural factors related to negotiation of paternity and ongoing responsibility for the child also serve as barriers to young men fulfilling their role as father.

Much more empirical research is required in SA on young fatherhood and to understand the role of culture and its impact on continued father involvement in children’s lives. However, other policy options may have to be considered to ensure paternal support for children. These include gender-based interventions that extend the repertoire of fatherhood beyond ‘providing’ to being ‘present and talking’, especially in impoverished conditions where unemployment and poverty is high. In addition, consideration should be given to legal child support arrangements, much like in the US, where legislative interventions have resulted in increased levels of paternal involvement among children of teenage mothers.

Interventions

In keeping with the multiple spheres of influence on adolescent sexual behaviour, a number of prevention interventions have been instituted in SA. These include school-based sex education, peer education programmes, adolescent friendly clinic initiatives, mass media interventions as well as community level programmes. While the focus of these interventions has primarily been on preventing HIV, they have conferred benefit to teenage pregnancy because of their impact on sexual behaviour. Separate interventions for teenage pregnancy and HIV are neither desirable nor feasible. To prevent pregnancy from being overshadowed by a focus on HIV, however, a distinct focus on teenage pregnancy is required. But the range, scale and reach, as well as the quality of implementation of programmes vary widely and have limited their impact on adolescent sexuality. In addition, the small number and lack of rigour of evaluation studies limit the conclusions that can be reached about the effectiveness of interventions. However, based on the growing body of evidence in both developed and developing countries, particularly with regards to HIV, recommendations for effective/promising approaches can be made. These need to be taken to scale to increase the reach and impact of programmes.

What is evident is that a magic bullet for teenage pregnancy does not exist. Given the multiple levels of influence on adolescent sexual behaviour, and, in turn, pregnancy, single intervention strategies by single sectors of society will not solve teenage pregnancy. What is required is comprehensive approaches within the home, the school, the community, the health care setting and at a structural level. In addition, while each sector should act within its strength and foster linkages with other sectors, an integrated strategy is required to ensure that all sectors act towards achieving a common goal.

As all young people will confront their sexuality at some point in time, universal access to information and skills are required early on to enable them to make informed choices. However, where conditions stack high and overlapping levels of risk among some young people, targeted and more intensive intervention strategies will be required. It is clear, and rightly so, that the sexual risk factors are often targeted in programmes because they are more directly related to pregnancy and HIV and are more amenable to change. However, what the study has demonstrated is that non-sexual risk factors such as relational (family structure, gender relations) and structural factors (education, poverty) are critical determinants in SA. Yet the thrust of our interventions has been on sexual risk factors. Without interventions that target relational and structural factors, substantive declines in the rates of teen fertility will not be achieved. In addition, sexuality is a shared activity between two partners. It makes little sense to empower women about their sexuality without concomitant efforts to empower men about equitable gender relations.

Although strong arguments exist for the thrust of interventions for adolescents to focus on prevention, the unabated and increasing levels of marginalisation of young people across a range of domains provide impetus for a more systematic focus on treatment, care and support. Even if we instituted the most rigorous prevention programmes, some young women will experience early pregnancy. Although remediation is costly and difficult to achieve, it far outweighs the costs to a society of lost human capital potential. No doubt, second chance programmes are being provided in SA and other developing countries, often by community-based organisations. However, available evidence suggests that they are few, and in all likelihood are small scale and seldom evaluated. A systematic and more formalised system of support is required for those who do experience early pregnancy.

As a support to comprehensive sex education in schools, an assessment of the availability of condoms in the community should be conducted. Where community availability of condoms to young people is low, consideration should be given to making condoms available through the school system.

A number of adolescents are at elevated risk for teenage pregnancy because of the social conditions in which they live. Markers of learners at elevated risk include those repeating grades, frequently absent from school, learners with a history of childhood sexual or physical abuse, learners who use/misuse substances and learners living under conditions of extreme poverty. An early warning system must be established such that teachers can identify learners at elevated risk and refer them to systems within the school or in the community for more individualised and intensive intervention.

Our secondary analysis of EMIS data indicates that higher rates of learner pregnancies are reported in schools located in poor neighbourhoods (measured by no fee schools and farm schools) and those in which age-mixing is significant (measured by combined schools), indicative of gender power imbalances. As part of a phased approach towards teenage pregnancy within the school system, interventions should be targeted at combined schools and those located in the poorest communities.

The traditional approach of health promotion within the school setting has been to focus on improving the health of learners to facilitate learning outcomes. However, given the significant protection that education can offer to health outcomes, improving both the quality and quantity of education may confer significant benefit.

Incomplete schooling is a significant risk factor for both pregnancy and HIV in SA. Instituting interventions that promote uninterrupted schooling may be an effective method to prevent early pregnancy and HIV. As financial concerns and high levels of repetition are two of the chief reasons for inordinate levels of dropout in SA, addressing the financial barriers to schooling and setting up a system for the remediation of school performance for those learners repeating grades may be effective interventions. Conditional cash transfer programmes have proven to be effective in improving school attendance in Mexico, Bangladesh, Nicaragua and Brazil. Plans are underway to test such a programme in SA with HIV as an outcome measure. Such an intervention may also confer benefit to teenage pregnancy but would need to be a distinct outcome measure of the trial.

When learners do dropout of school, a systematic process is required to re-enrol them in school or in alternative systems of education. To dramatically increase the number of young people enrolled in alternative pathways such as Further Education and Training or Adult Basic Education and Training, however, a number of gaps need to be addressed. These include ensuring that programmes are adequately resourced, provide quality education services, and are reframed as legitimate and credible systems linked to mainstream pathways (HSRC, 2007). In addition, alternative systems must offer viable exit opportunities for participants by cohering with further education and economic opportunities. Young people using alternative pathways rarely experience difficulties in only one aspect of their lives (Yohalem and Pittman, 2001). They often require support on multiple fronts. Service provision must be comprehensive and tend to development in a holistic manner. The structure of second chance programmes must also be flexible to accommodate the economic imperatives and family commitments that make young people turn to alternative systems.

Service learning that involves community service that is either voluntary or linked to the school curriculum has shown positive effects on sexual activity and pregnancy in the US even when programmes have not addressed sexuality directly. Instituting such interventions may be a cost effective youth development strategy that is in line with the goals of the second generation youth policy in SA. These include promoting community participation among school going learners and providing much needed work experience for young people – a prerequisite for employment, while concomitantly offering protection to reproductive health outcomes.

Second chances

As in most other countries that have developed flexible school policies regarding pregnancy, policy effectiveness in SA is limited by the extent to which it is consistently implemented. In particular, the core constituency – young men and women, need to be empowered about their right to education to enable them to demand access when provision is denied.

Much advocacy work is also required to ensure that the gatekeepers of education - principals, teachers and fellow learners, buy into the policy to reduce the stigma that often turns young mothers away from the doors of learning.

An enabling policy needs to be supported by a programmatic focus that addresses the barriers to learning. Chief among these is ensuring the prompt return of girls post-pregnancy into the schooling system. The suggestion of ‘up to a two year waiting period’ before return to school in the Department of Education learner pregnancy guidelines, may be counterproductive to both maternal and child outcomes. In addition, catch-up programmes with respect to the academic curriculum will need to be provided and, in particular, remedial education to improve school performance that often leads to dropout.

Strong referral networks are also required with relevant government departments and other community structures that can support learners with childcare arrangements, access to reproductive health services - in particular access to contraception to prevent second birth - child support grants and to develop appropriate parenting skills to mitigate the intergenerational transmission of early parenthood. While a mass-based system is effective for the prevention of pregnancy, teenage mothers benefit more from intensive, individualised support. Setting up a one-on-one relationship with an educator or community organisation will assist teen mothers in negotiating the range of new economic, educational and social imperatives that they face.

Other sectors

Communities

There is ample empirical evidence to show that when young people are excluded from mainstream systems such as education, they are at increased risk for high risk behaviour. This is clearly evident in SA with regards to the link between school dropout and risk for pregnancy and HIV. While interventions are instituted to prevent recurring marginalisation from the school system, concomitant efforts are required within the community to support young people at high risk for pregnancy. But community participation among young people is very low in SA and the reach of large-scale interventions in the community such as loveLife is not optimal. Expanding participation in community-based interventions represents a potential growth area in responding to adolescent sexual and reproductive health in SA although more rigorous evaluation studies are require to demonstrate their efficacy.