Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

In this document topics covered which are ,FROM HOPE THROUGH TURMOIL TO UNCERTAINTY,INTRODUCTION,The intrinsic role,Comparisons and lessons

Typology: Study Guides, Projects, Research

1 / 33

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

A discussion paper contributed by Nikola Aranđelović & Professor Tony O’Rourke for the Workshop “The European Union and Southeast Europe after 2004” to be held at the University of Stirling between 19 and 20 March 2004.

The authors, who together have experience as practitioners in the financial sector as well as teaching, research and analytical expertise in the Serbian situation, would put forward the view that a study of the banking system cannot be omitted from any consideration of the political and economic future of the transition economies of South-East Europe. Why?

1.1 The intrinsic role There is a powerful argument that failing to include banking in the initial process of transformation and change can have a potentially difficult effect on the completion of the reform process. It is interesting to recall that the Czech government embarked on a programme of rapid privatisation from 1993. This involved a substantial transfer of ownership via a classic Mass Privatisation Programme. However, the state-owned banking sector was largely ignored in this process. Privatisation of enterprises via MPP vouchers resulted in citizens selling their holdings to investment funds, who became owners of large stakes in the Czech economy. After a period of rapid consolidation, the primary owners of the funds became the banks, and thus the state – through the banks – was able to continue to influence enterprise. The Czech banks were not privatised substantially until the end of the 1990’s.

In Hungary, bank and financial sector privatisation proceeded on almost parallel lines with privatisation of enterprises. The result has been that Hungary has one of the best structured and stable banking systems (albeit under 90% foreign control) in the CEE economies.

In Serbia, bank privatisation was effectively removed from the remit of the 1996 privatisation programme – we must assume because the powerbase of the banks, holders of huge amounts of enterprise and inter-enterprise debt, was too important for the Socialist Party and its electoral allies to lose control over. It is also clear that under Milošević, domestic savings were used as a means to support external political-military intervention; also under Milošević, banks had an important role as a means of channelling scarce resources and of boosting failing industries. Equally, we should not forget that in the early stages of the post-2000 reform programme in Serbia, restructuring of the banking system also provided useful weapon to use against financial backers of former regime (eg Karić and Astra banka) or to realign financial systems (bankruptcy of the big banks which were backers of the old regime).

1.2 Comparisons and lessons We should not also lose touch with the view that what happened yesterday in one region, may happen tomorrow elsewhere. For observers of the banking systems in some of the poorer and less advanced former Soviet republics (specifically the CIS-7 grouping), there are immediate and very similar parallels. A very obvious example is taking the relationship of the Milošević regime towards the banking system in Serbia and comparing it with the actions of President Islam Karimov in Uzbekistan. Current events in Uzbekistan seem frighteningly familiar to those of us who were involved in the Serbian banking system during the 1990’s. In this sense, study of the banking system provides a keen and valuable barometer of socio-economic value structures.

1.3 Structure of the paper In this paper we will be examining the development of the Serbian banking sector and its relationship with the Serbian state, as well as the extent to which it sought to emulate or harmonise with general European banking trends.

2.1 Contrasting models of socialism It is important to have in mind that in banking terms, as well as in economic and structural terms, there were significant differences between the Yugoslav model of socialism and the Soviet/Comecon model which applied in all other so-called “Eastern Bloc” countries.

In the Soviet bloc the banks acted as functionaries of the government and the party in allocating financial resources to the productive process. There was no intermediary role between savers and borrowers and the banking system was generally specialised into trade institutions, public savings banks and investment banks. There was also no distinction between the commercial banks and the central bank. In the Soviet bloc countries there was no financial market as all liquidity requirements were met by the central command structure. The only lapse from the general model was found in Hungary. By 1987, economic reforms driven by the Hungarian Communist Party had introduced a two-tier banking model and liberalised the rules controlling the banking system to enable the start of classic commercial banking services. This explains to a great extent, Hungary’s role as the most advanced model of banking reform in the CEE countries.

In the pre-1991 Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia, banks were permitted to operate as a financing resource mechanism for enterprises. The banks operated on a republic basis and in general were owned by the socially- owned enterprises. The only exceptions were two federation-wide specialist banking institutions – the system of Jugobanka which had banks in every republic and autonomous republics and the YUBMES import/export bank. As the banks gathered the foreign exchange savings of citizens, they were also able to carry out commercial lending activities as well as participating in international financial functions. Unlike the situation in the Soviet bloc, there was a two-tier banking system and both the federation-wide National Bank of Yugoslavia (NBJ) as well as the eight republic central banks had a considerable role in the banking system as prudential supervisor, regulator of licensing and in oversight of monetary and economic policy. It should be noted that each of the 6 constituent republics and the 2 autonomous republics of Serbia (Kosovo-Metohija and Vojvodina, which in 1989 became autonomous provinces) had their own central banks. Furthermore, it is interesting to recall that in the early part of 1967, the Association of Serbian & Montenegrin Banks established an inter-bank money market. The role of that organisation was to assist banks in managing liquidity and subsequently in operations with securities. Compared with other socialist economies, this was an advanced step for a banking system to take.

We should add that although the banking system was regulated on a federal basis and had as its pivotal centre the NBJ, the actual development and role of

the banks varied from republic to republic and was to a certain extent reflective of the economic circumstances and level of development in each republic. Although Serbia was the largest republic in terms of population, its banks represented only around 37.5% of the total banking assets of the SFRJ.

2.2 Legislative reforms from the Marković programme^2

From the later part of 1988 and through 1989 the Yugoslav federal government of Prime Minister Ante Marković commenced a programme of new economic reform which sought to follow western market concepts. In practical terms this was the start of the Yugoslav transition process towards a market economy. We should have in mind that at that time Yugoslavia was ahead of a number of European countries which were members of the then European Economic Community. We should further understand that the Yugoslav form of socialism was highly decentralised and had adopted a number of free market concepts, including the retention of profits within the self-managed, socially-owned enterprise.

As part of the package of new economic reforms which Prime Minister Marković pushed through the federal parliament, was included a number of laws which related to the reform and revitalisation of the financial sector. The major and most significant laws were those relating to :

The major impact of this legislation was to provide for the organisation of a developed banking sector, money and capital markets across the entire federation. As a result of these laws, money and capital markets appeared in Serbia as well as in Slovenia and Croatia. It should also be noted that these reforms were supported by inputs from the IMF and the World Bank.

The 1989 legislation ensured a strong role in banking regulation and prudential supervision for the NBJ. During 1989 and first half of 1990 all banks had the obligation to obtain a licence from the central bank and were required to accept the supervision of the NBJ in the methodology by which

enterprise to access financing. This closely symbiotic nature of the bank/enterprise link, where the enterprises were both the majority owners as well as the majority debtors proved to be economically destructive in the Serbian environment

3.1 Banking in Serbia 1991- From June 1991, we are able to distinguish a specific policy which was followed by the NBJ, although in effect its remit as a central bank only applied in Serbia and Montenegro, and partially in BiH and Macedonia. By October 1991, the republic national banks of Croatia and Slovenia had become independent entities in regard to banking supervision, monetary control and currency issue. The outbreak of war, briefly in Slovenia, and then more extensively in Croatia and BiH through 1991-1995, had an immense and painful effect on the Serbian financial system. International sanctions on what became the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SRJ – the third Yugoslavia) had an instrumental effect in the collapse of production and trade, the financing of enterprises and mega inflation in 1993. During this time the level of criminal activities and the related black economy grew dramatically. Connected to this was rampant corruption, with the connivance and implicit support of the political leadership.

We also require taking account of the level of criminality, which began to appear in very significant levels during 1992-1994 and onwards. As inflation increased, together with the effects of economic sanctions in the provision of basic products, the level of criminal elements and those exploiting the needs of ordinary citizens multiplied. It was a period of the classic primary acquisition of capital; whilst the professional and business middle classes began to suffer serious hardships and saw their living standards decline abruptly, those engaged in “informal” trading, “shuttle” trading across frontiers and the organisation of the black market became hugely wealthy. Because of their connections with the regime and their financial inputs into the regime, a whole class of new entrepreneurs emerged. For them, engagement in banking activities was another form of wealth creation and generation.

Towards the end of 1992 and during the first half of 1993 there also appeared around 2,000 financial institutions, described as “savings organisations”, which were in effect pyramid schemes operating with legal sanction and with strong links into the black economy and the criminal world. Even the Serbian state was involved, although not openly, in the operation of two such pyramid savings organisations (Dafiment banka and Jugoscandic savings organisation). The inevitable and highly public collapse of these organisations prompted high levels of public protest, and as a result the National Bank, at the end of 1993, suddenly forbade their activity by declaring that “saving organisations” were required to obtain an NBJ licence for their operations. Of the 2,000 organisations, only ten gained an NBJ licence, whilst the rest ceased activity – albeit that the capital they had gathered was retained by them without any subsequent legal process for recovery. A small number

the banknote was first issues, on 23 December 1993 it had a value of about DEM 10; two weeks later it had lost 99% of its value as was worth 10 pfennigs.

Shortly before the end of 1993, the Federal Government re-denominated the dinar in the relation 1: 1,000,000,000 effective from 1 January 1994. This re- denomination was a technical step, simply to make easier the turnover of currency. Cash registers, for example, had simply been unable to cope with the huge number of zeros.

3.3 The Avramović Programme At the beginning of 1994, faced with the crippling effects of the existing state policy, it was decided to initiate a new reform programme of monetary reconstruction and economic rehabilitation. The person chosen to head this project was Dr Dragoslav Avramović, an IMF economist who was certainly better known in global circles than in Serbia. Those of us who had the benefit and privilege of meeting the late Dr Avramović, will remember a man of great humility but tremendous intellect who was able to galvanise a team of domestic economists to kick-start a programme of reform. Appointed as Governor of the NBJ, Dr Avramović initiated a highly popular programme of inflation reduction. His introduction of the new dinar on 24 January 1994, with a fixed parity at YUD 1 = DEM 1, stopped overnight the inflationary spiral. Given the complete “deutschmarkisation” of the economy, where it was even possible to buy goods with pfennigs, such a simplistic evaluation proved understandable and popular. For the banking system, which on the whole had effectively lost its assets during the 1992-1994 period, there was the chance to begin afresh and to seek to operate as banks in other transition economies moving towards a free market.

One of Dr Avramović’s immediate policies was to suspend the printing of currency at the Topčider facility. The NBJ thus effectively ceased the issue of primary money and sought to establish some form of control and supervision over the banking system. In general, we can see that this policy brought immediate relief and halted the super-hyper inflationary spiral. At the same time, Dr Avramović also sought to engage experts from abroad in providing inputs as to how the transformation of the economy could be engineered – including the reform of the banking system. We have to be aware that by December 1994, the banking sector remained in a state of distress; a situation that the Avramović reforms had been unable to alter. According to data collected by the NBJ, the average bank balance sheet reached a total of € 118 million; only 7 banks had a balance sheet total greater than € 510 million and even the average for those 7 largest banks was only € 1,144 million. In such a situation, with such a low degree of capital adequacy, it was open to many individuals to found banks or other financial sector organisations.

As we have seen, the problem was that many of the banks were under the political control of the regime and furthermore the regime itself was committed to bribery of the population through the payment of pensions and social benefits, as well as the issue of soft loans to favoured enterprises. In the early part of 1996, pressure from the politicians in the regime became very intensive and subsequently on 15 May, Dr Avramović was dismissed as Governor of the NBJ and replaced with a political appointee. It is of note, that due to a lack of monetary diligence, the authorities allowed the official rate of exchange to vary from the 1.00:1.00 rate set by Dr Avramović, to 3.30:1.00 and to 6.00:1.00, with an “over-the-counter” rate of around YUD 30 to DEM 1.

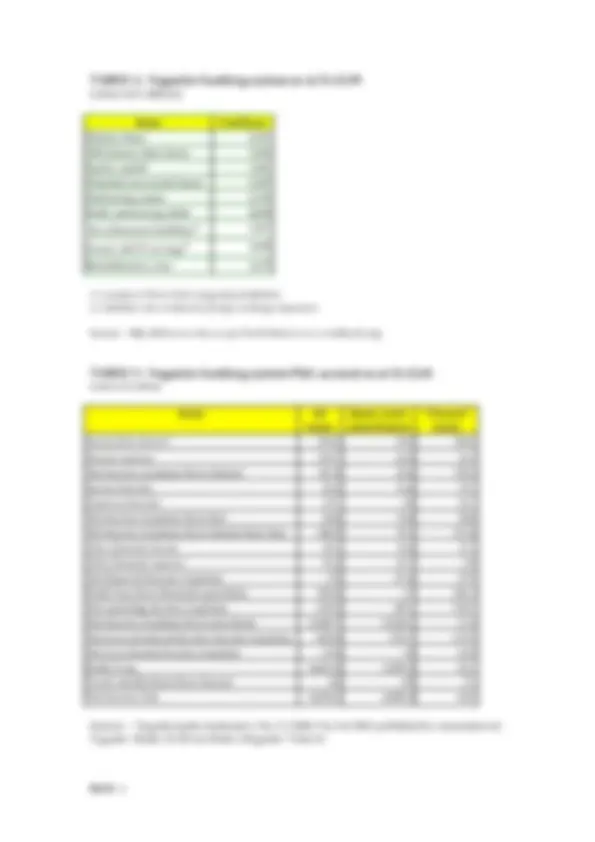

3.4 Post-Avramović The period following the replacement of Dr Avramović signalled a return to less than realistic policies and ambitions in the banking sector. During 1995, the NBJ had exercised a more stringent policy in regard to the holding of banking licences. At that time 10 banks within the federal state had their licences withdrawn (5 in Serbia, 5 in Vojvodina). Yet in the early months of 1996, a number of new banks appeared. By April 1996, shortly before the departure of Dr Avramović, the total of banks in the SRJ stood at 111 (compared with 126 in the previous year – see Table 1).

Illiquidity problems in 1997 became very serious and more widespread than in the banking sector alone; it appeared in all sectors of industry given the close relationship between the banks and socially-owned enterprises. As at 30 June 1997 according to the financial statements of all enterprises in the Republic of Serbia, total turnover was YUD 2.6 billion but losses were recorded at YUD 9.0 billion. This data covered 21,494 registered companies employing 871,557 – a significant proportion of the Serbian enterprise sector. In all sectors of industrial production, with the exception of wood processing, expenses were greater than income. The major problem was the financing of cash flow; enterprises were only able to self-finance some 29.8% from sales income, whilst 70.2 % was financed from borrowing (38.7% from long term financing and 31.5 % from short term financing). As at 30 June 1997 19, companies (90.6% of all legally registered enterprises) had their accounts blocked at the on the central payments system because they had insufficient funds to meet all their obligations. These obligations, as at 30.06.97 reached the total sum of YUD 8.6 billion, a 72.7% year-on-year increase, which is a formidable increase in enterprise and inter-enterprise debt. (Data on the general degree and structure of liquidity is contained in Tables 3 and 4 below). Despite this situation, the monetary policy of NBY was very restricted and problems with liquidity were evident in a large number of banks during 1997; the result was that 3 banks had their operating licences suspended by the NBJ license in July 1997.

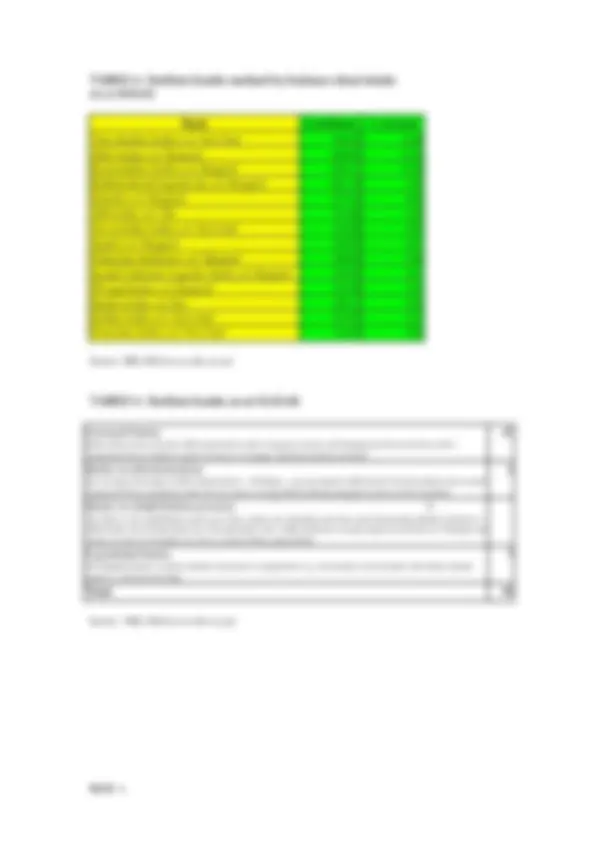

3.5 Comment This period saw the final destruction of the pre-1991 banking system in Serbia. The events surrounding the NATO attack on Serbia resulted in a situation where by the end of 1999 (see Tables 4 & 5) the banking system was in what could only be described as a parlous state. Twenty-eight banks had negative equity capital and the four big banks had potential losses which were greater than 50% of the total assets of the entire banking sector. Furthermore the banks were riddled with inefficiency and overstaffing; 57% of all bank staff were employed in the three largest banks, which were undoubtedly the most inefficient and the most debt-ridden. We should also have in mind that the level of foreign currency capitalisation (i.e. “euroisation” or “dollarisation”) was very high. At the end of 1999, it is estimated that 86.9% of bank assets and 83.5% of bank liabilities were in foreign currencies. The value of YUD holdings had been effectively destroyed by war, economic isolation and financial chaos.

4.1 Background During the last 3 years, the National Bank of Serbia (formerly National Bank of Yugoslavia) has moved away from the subordinate role it had to the Milošević dictatorship and a financial system based on corruption and criminality. During the period from 1990-2000, the central bank had operated initially as a war chest for military aggression in Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia & Hercegovina, as a form of bizarre economic-financial engineering and latterly as an instrument for financial repression. Economic isolation as well as a financial turmoil marked the highest inflation in modern history, left the economy in a desolate shape. The last comprehensive analysis of the banking sector carried out in 1989, identified high cumulative potential losses in the range of USD 9-11 billion in the banks of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

As we have seen, the hyperinflation and then super hyperinflation, which occurred during 1989-1993, effectively ruined the Serbian banking system. Unlike the other republic banks, international sanctions on Serbia and Montenegro closed off access to the restructuring and stabilisation programmes of World Bank, IMF and EBRD. By the end of 1993, the banking system had clocked up around EUR 1.8 billion in losses. By the end of 1997, it is estimated that losses were running at EUR 100 million per month. In addition to this, it was estimated that at June 2001, the total debt of enterprises to the banking system was around EUR 1.3 billion. Of this 40% was irrecoverable, 50% was bad debt with some possibility of partial recovery and 10% was recoverable.

4.2 First steps The first realistic steps towards the restructuring of the system and entire financial apparatus began in November 2000 with the appointment of a new Governor of the National Bank of Yugoslavia (NBJ). Dr Mlađen Dinkić was previously co-ordinator of the opposition group of economists - G17 Plus. The new team at the NBJ were able to establish that :

distributed to all depositors with deposits of less than EUR 3,300. In addition, the Serbian government commenced a programme by which holders of frozen foreign currency accounts could obtain tradable EUR-denominated bonds in exchange for those accounts or immediate cash payments at the Nacionalna štedionica banka.

4.4 Mergers & acquisitions and foreign bank entry The pace of M&A activity has been strong over the past two years. This has included acquisitions in order to expand branch networks as well as mergers in order to boost capital adequacy. The second largest Serbian domestic bank, Delta, bought Tigar banka of Pirot (financial subsidiary of the Tigar tyre enterprise); 12th^ ranked player Jubanka, bought Inoprom banka Beograd and Jugobanka Užice to expand network; 11th^ ranked Novosadska banka of Novi

Sad acquired the regionals Vršačka banka of Vršac and Dinara banka Beograd.

The first foreign bank with a full operating licence had been Sociétè-Génèrale Jugoslavija, a fully owned subsidiary of the French Sociétè-Génèrale group. Sociétè-Génèrale Jugoslavija was established in 1990 and maintained a presence throughout the following decade, although operations were suspended at a number of critical times. The French bank commenced corporate operations in January 2001 and personal banking activity in May

During 2001 other foreign banks quickly entered the corporate and personal banking markets – HVB banka (owned by the HypoVereinsbank Group of München), Hypo-Alpe-Adria banka (owned by Hypo-Alpe-Adria AG of Klagenfurt – a joint venture of the Kärntner Landesbanken and Gräzer Versicherungen) and Raiffeisenbank Jugoslavija (owned by Austria’s agricultural savings bank - Raiffeisen Zentralbank). HVB also integrated into its operations, the corporate banking activities of Bank Austria-Creditanstalt, now part of the HVB group. HAA has also broadened its base by buying Depozitno Kreditna banka of Beograd.

In addition a number of Serbian banks have gained substantial foreign investors. 14th^ ranked Continental banka of Novi Sad is now almost wholly owned by the Slovenian Nova Ljubljanska banka (itself an affiliate of Belgium’s KBC). Meridijan banka in Novi Sad (partly owned by Belgian and Luxembourg interests) acquired the Romanian-owned Bankcoop Vršac. At the end of last year, Prva Preduzetnička banka Beograd came under the almost complete ownership of LHB Frankfurt (majority owned by the Slovenia’s Nova Ljubljanska banka) and changed its name to LHB Beograd. Before that in September 2003 the Austrian Volksbanken Group acquired the

capital of Serbian Trust Banka, which has been renamed Volksbanka Beograd. Finally mention should also be made of Pro-Credit Bank (formerly the Micro- Finance Bank), which was established in the early months of 2001 by EBRD and a number of international donors, to develop loan facilities for SMEs and has a network in 9 Balkan and Eastern European countries.

4.5 Supervisory strategies of the NBS The NBS has developed its supervision function to meet the following operating targets:

In its process of meetings these strategic goals, the NBS has commenced a policy of :

5.1 No halt to the reform process Looking to the future is difficult task at the moment, given the somewhat volatile nature of Serbian politics. Where government is being formed from conflicting and contrasting groups, posts such as governorships of central banks and chairmanships of key committees, frequently become political prizes. In such a situation there is concern in regard to the extent to which the Governor and the Managing team of NBS are able to remain isolated from political influence, as well as whether the existing team will stay intact or be dispersed. We have little doubt that the future of Serbian banking depends very much on a degree of stability and continuity. We also believe that the entire banking reform process can not now be stopped. The system has been regularised and harmonised with general European standards. Banking is now at critical point where it will develop through the transition process to support and dynamise the market economy. Too much time has been wasted since 1989, when the prospects for Yugoslav banking to be a leader among transition economies were high. The general process and impetus of change in the Serbian banking system is also well advanced; for example, Serbian banks must for the first time in their history prepare and publish their Annual Reports and Financial Statements for the 2003 financial year in conformity with International Accounting Standards. By utilising such standards the financial results of banks, their ownership and governance, will be changed and also become far more transparent. That action was one of latest steps in implementation of international standards in Serbian banking system as prior to that all banks had the obligation to obtain no later than 31 December 2003 a minimum monetary capital adequacy equivalent to € 10 million. It is indicative of the new strength of the banking sector that all licensed banks were able to meet that requirement.

5.2 The effects of foreign banking penetration The process of penetration of foreign banks and owners into the Serbian banking system is not as yet close to its finish. Under existing law, the Republic of Serbia has the obligation to sell its ownership in three of the largest banks to domestic or foreign private investors. These banks are Vojvođanska banka (50% state equity); Komercijalna banka (40% state equity) and Jubanka (35% state equity). In each of the former socially-owned banks the state’s equity ownership is due to their takeover of the obligations of those banks to the Paris and London creditors clubs in 2002). In addition, the state has smaller equity stakes of between 10 and 20% in another ten banks. The penetration of foreign banks through acquisition of some of the larger banks will be a strong indicator that the Serbian banking system is developing in the right way.

Certainly over the past three years, the penetration of foreign banks, whether through acquisition or green-field entry, has improved the quality and service

delivery of the domestic banks. Over the past year many new bank products have appeared from domestically-owned Serbian banks; these include the new domestic credit card – DINA card. Operations with “plastic money” and electronic payments systems were almost forgotten in Serbian banking system, but now the majority of domestic banks are offering international credit cards from Visa, American Express, Diners or Mastercard/Eurocard as well as debit/payment cards (Delta/Electron, Maestro and domestic systems).

The other profound indicator of change over the past year has been the rapid increase in various types of Pension, Life Assurance and Health Insurance products which were effectively unknown in Serbia previously. Many large domestic financial services companies which are active in banking and insurance (e.g. Zepter and Delta Holdings) have started to develop bankassurance activities. Many observers would see this as a reaction to the fact that the many foreign entrants (e.g. HVB, SocGen, HAAB) are accomplished bankassurance operators. This is also symptomatic of the rapid development of retail, consumer-oriented banking, where banks become in effect financial supermarkets offering financial and investment advice, home and e-banking products, savings and loan facilities. Even the notion of consumer loan products was something strange to the Serbian domestic banking sector prior to 2002.

5.3 Corporate banking and capital market activity The foreign banks initial entry methodology had tended to be through corporate banking services for foreign clients and for blue-chip domestic clients. However, a number of more specific products, such as leasing have appeared. Although leasing has been spearheaded by the foreign banks, there is every indicator that Serbian domestic banks and specialist financial institutions will begin to offer a range of leasing products for companies. Account should also be taken of the massive potential for the use of leasing in the small business sector as a means of reducing capital expenditure and enhancing tax efficiency.

Many banks are planning to develop their services in area of capital markets operations, especially as custodian banks. The implementation of the new Securities Law in Serbia began on 1 October 2003; this places an important role of the provision of custodial and related back-office services, but will be a new and potentially attractive business for domestic banks. The intention of the new Securities Law is to develop role of the banks at the capital market. A specific area of development is in the development of Investment Funds, both in relation to privatisation issues and as a medium for the dynamisation of domestic savings. Those with strong involvement in the capital market over the past 15 years, have been pushing for a law on investment funds, as such a development is highly necessary to the growth and survival of the Serbian