Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

This thesis explores the relationship between teacher quality, working conditions, and retention in the education sector. research on the disproportionate impact of good teachers on poor pupils, the response of teachers to incentives, and the impact of administrative tasks on workload. It also highlights the limitations of existing research and the need to consider variables such as personality type, self-efficacy, social networks, and job values in predicting teacher retention.

What you will learn

Typology: Study notes

1 / 117

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

I, Sam Sims, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis.

The discoveries made in this PhD can be put to beneficial use in several ways. The Department for Education regularly states that teacher retention has been broadly stable for the last twenty years. Contrary to this, Chapter 1 demonstrates that the decline in early career retention is a major contributor to the current teacher shortage. I have recently written about this in the tes (Sims, 2018a). The Department’s policy should shift to reflect this fact by placing a stronger emphasis on retaining more teachers, rather than just trying to increase recruitment. Chapter 3 identifies robust school-level correlates of teacher job satisfaction and turnover intentions. I am currently working with the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL) to pilot a shortened version of the questionnaire used in Chapter 3 to help 14 schools self-assess the quality of working conditions they provide for their teachers. The aim is to help schools identify and address areas in which they have weaknesses. If the pilot proves a success, then ASCL plan to offer this service to their full membership in over 18,000 schools. Chapter 4 reports on an evaluation of the National STEM Learning Centre professional development courses for science teachers. The results from this evaluation are now being used by STEM Learning as part of the evidence base in their bid to have public funding for the programme renewed. This research was covered in the Times , the i , tes and Schools Week. Finally, Chapter 2 established that just four variables are able to identify individuals up to four times more likely to enter the teaching profession than the average graduate. Given the current shortage of teachers, this information can be used by policymakers to improve the targeting of marketing aimed at increasing recruitment.

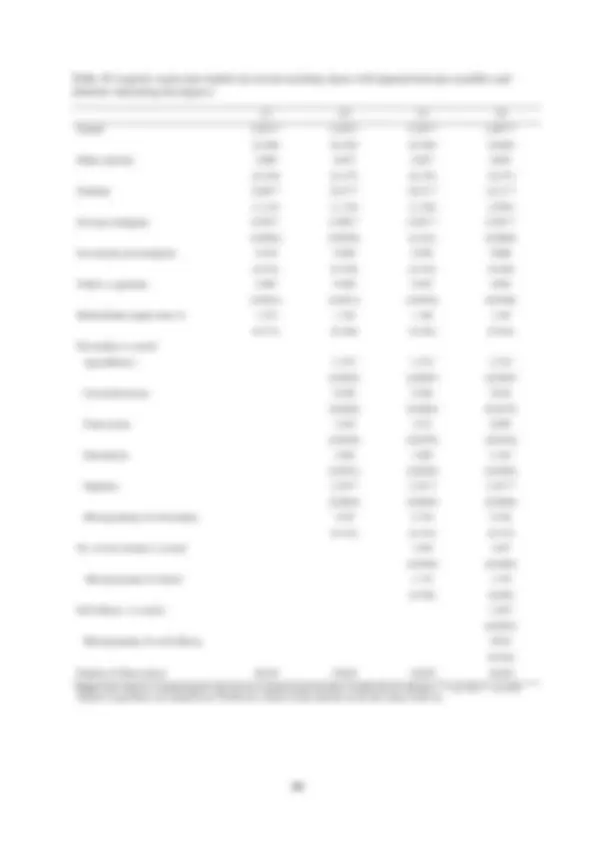

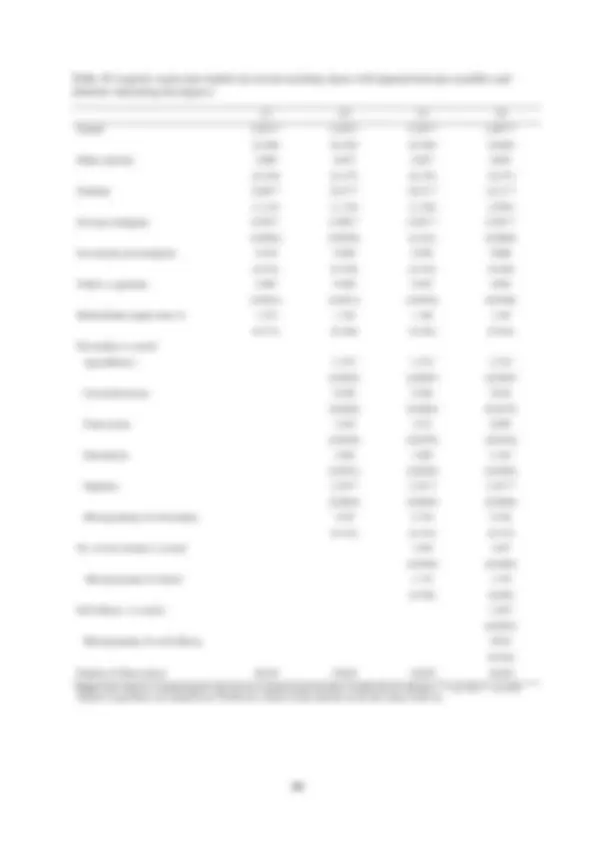

Table 24: Pairwise correlations between the complex scale scores used in the international modelling

Teachers have an important influence on their pupils. A one standard deviation (SD) increase in teacher quality is associated with a 0.1 to 0.2 SD increase in pupil attainment (Burgess, 2015). This is a strong relationship, at least when compared to other school level inputs. Indeed, Hanushek claims that “ no other attribute of schools comes close to having this much influence on student achievement ” (2011, p. 467). Good teachers improve equity as well as efficiency, because they have a disproportionately large impact on the attainment of poor pupils (Hamre & Pianta, 2005; Slater et al., 2012 ). Teachers also have an important influence on their pupils’ wider socio-emotional skills (Jackson, 2016; Kraft, 2018). It is perhaps not surprising then that the effects of good teachers can be detected in their pupils’ earnings long after leaving school (Chetty et al., 2014). Ensuring a sufficient supply of high quality teachers should therefore be a priority for education policymakers. Despite this, shortages of qualified teachers are a widespread and recurring problem in advanced economies (Dolton, 2006). The 2013 Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) collected data from a representative sample of school principals in over thirty countries. When these school leaders were asked about the biggest constraint they faced in improving the quality of instruction, the most common response was the lack of appropriately qualified staff (OECD, 2014). Faced with such shortages, school leaders are forced to lower recruitment standards, increase their use of temporary teachers or increase class sizes (Smithers & Robinson, 2000). This has prompted organisations including the UN, World Bank, OECD and the EU to warn that teacher recruitment efforts need to be stepped up (Figazzolo, 2012; Ranguelov et al., 2012; Schleicher, 2011). This thesis aims to address the problem of teacher shortages by providing new evidence on why people enter and exit the teaching profession. In Chapter 2, I use household panel data to analyse long terms trends in the types of people who become teachers and then utilise the rich data to conduct detailed modelling of the reasons why people choose to become teachers. In Chapter 3, I switch focus to investigate teacher retention, utilising the TALIS survey data to develop a set of working conditions measures which allow me to model the determinants of teacher job satisfaction and desire to move school. Then in Chapter 4, I focus on identifying the causal impact of one important aspect of working conditions, professional development, on teacher retention. Chapter 5 concludes by summarising the findings of the research. This thesis is part of a wider programme of research which I have been conducting on the teacher labour market, including work on socio-economic inequalities in access to good teachers (Allen & Sims, 2018a; 2018b), the quality of teacher working conditions across countries (Zieger et al., 2018), the effects of targeted salary supplements on early-career teacher retention (Sims, 201 8 b), and the

effect of leadership training (Knibbs et al., 2017) and school inspections (Sims, 2016) on teacher retention.

Teacher shortages are a cyclical phenomenon. Long run cycles occur as demographic bulges, such as the post-war Baby Boom, work their way through the age distribution (Dolton, 2006). As these demographic bulges reach school age the number of pupils increases, thus increasing the demand for teachers; as they reach adulthood and enter the labour market, the supply of teachers increases (see Chapter 2); and as they reach retirement there can be sharp contractions in the supply of teachers. The post-war baby boom generation (born 1945-64), for example, began attending school in the fifties, began entering the labour market in the sixties and are now entering retirement (Callanan & Greenhaus, 2008; Chevalier & Dolton, 2004 a). England and Wales experience peaks in the number of live births approximately once every twenty to thirty years (ONS, 2015). As well as being influenced by demographic cycles, teacher shortages are also related to economic cycles. When recessions occur, employment opportunities in teaching are relatively prevalent. In the two years immediately following the 2008 recession for example, there was a 30% increase in the number of graduates choosing to train as teachers (Howson & McNamara, 2012). In periods of economic expansion however, relative wages in other occupations rise, incentivising graduates to choose occupations other than teaching (Chevalier et al., 2007). Demographic and economic cycles therefore conspire to ensure that teacher shortages are a recurring public policy challenge. England is currently experiencing something of a perfect storm in terms of the demographics and economics of teacher supply. First, a demographic bulge is currently working its way through the secondary school-age population (DfE, 2016), with the result that there is forecast to be a 13% increase in pupil numbers between 2015 and 2024 (Lynch et al., 2016). Second, Baby Boom teachers have now largely retired, increasing the need for additional recruitment (Chevalier & Dolton 2004a). Third, England has recently experienced an improvement in graduate (un)employment (DfE, 2017 a) and an increasing gap in median earnings between teachers and other professions in the majority of regions in England (STRB, 2017), drawing graduates away from teaching. It is perhaps not surprising then that there is a growing shortage of teachers in England. The Department for Education (DfE) uses a sophisticated model to estimate the number of teachers it will need to train each year in order to ensure a sufficient supply of classroom teachers. On the supply side, the model takes into account all flows into and out of the profession, which vary depending on the state of the economy and the age profile of the teaching workforce, among other factors. On the demand side, the model takes into account the number of pupils of school age, determinants of which include the number of births and net migration patterns. The difference between these two numbers can then be used to calculate the number of teachers that need to be recruited each year in order to

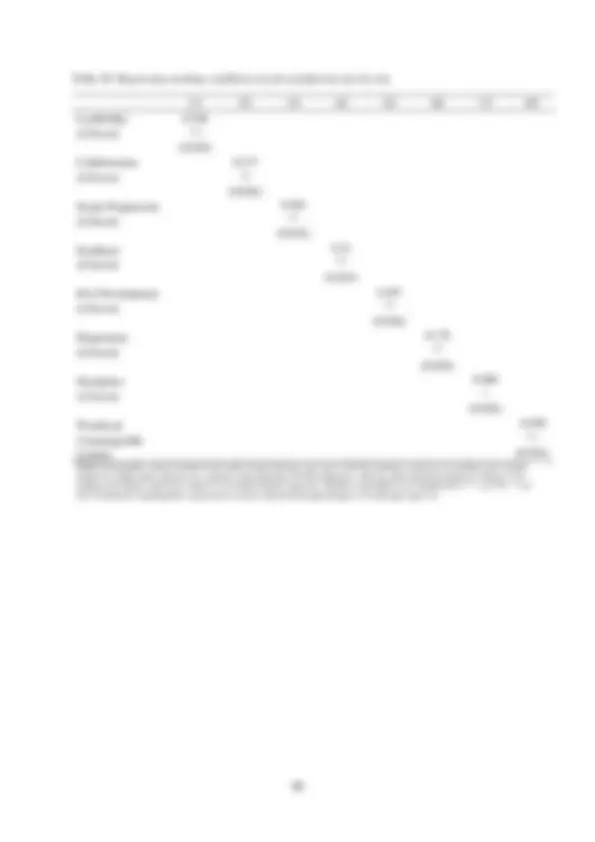

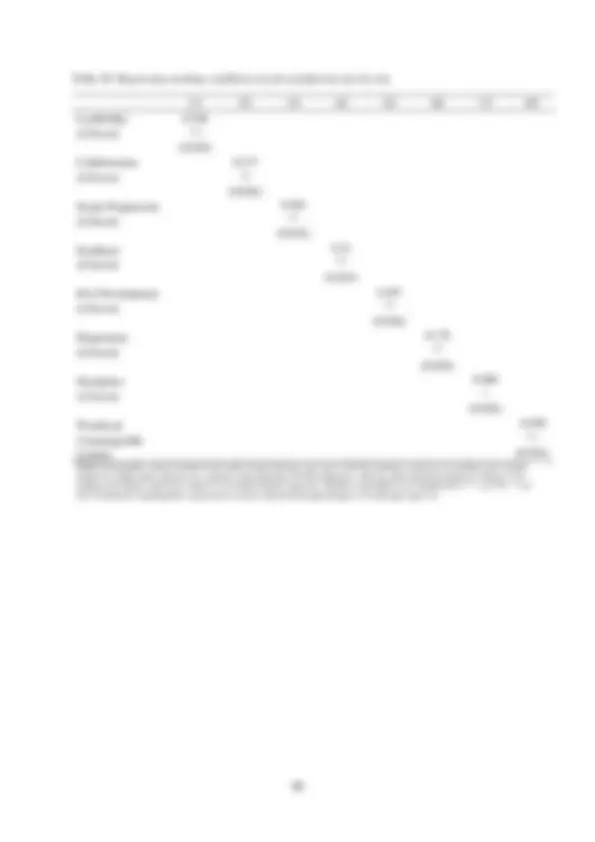

biology and physics in 2014; chemistry in 2015; then English in 2016. By 2017, the only EBACC subject not in shortage was history. Among non-EBACC subjects (not shown here for space reasons) art, music, religious studies and business are also in shortage. Indeed, physical education is the only non-EBACC subject included in the data which was not in shortage in 2017. Figure 2 : Teacher balance by subject (STEM) 2010 - 17 Notes: Source: Initial Teacher Training Census Main Tables and Teacher Supply Model. Figures for computing first reported for 2012/13. Figures for the three sciences first reported separately for 2014. Despite being foreseeable based on demographic and economic trends, the current teacher shortage has an additional, less predictable component: declining early-career retention. Figure 4 shows retention of each cohort of newly qualified teachers (NQT) in England. The 2005 to 2009 cohorts follow a broadly similar trajectory. From 2010 onwards however, there is a clear decline in retention, with each new cohort having a steeper downward gradient than the last. Early-career retention is worse among shortage-subject teachers such as scientists (Kelly, 2004; Worth & De Lazzari, 2017 ), perhaps because they face higher outside pay ratios (MAC, 2016). Early-career retention is also worse among certain initial teacher training routes such as Teach First, which has expanded over this period (Allen et al., 2013). This decline in early-career retention is materially significant. As shown in Table 14 in Appendix A, if early-career retention rates had been frozen at 2009 levels, there would now be an additional 4,398 teachers working in England. To put this figure in context, the total shortfall of EBACC teachers is currently 2,080. Declining early-career teacher retention is therefore a major contributor to the current teacher shortage.

Figure 3 : Teacher balance by subject (Non STEM) 2010- 17 Notes: Source: Initial Teacher Training Census Main Tables (see: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/statistics- teacher-training) and DfE(2013). Figure 4 : Proportion of NQT cohort retained Notes: Source: School Workforce in England 2017 (see: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/school-workforce-in- england-november- 2017 )

2017; Micklewright et al., 2014 ). It is these sorts of administrative tasks and the overly detailed, bureaucratic nature in which they are conducted which teachers identify as being the aspects of workload that they like least (Gibson et al., 2015). This research has prompted policymakers to work with unions and school leaders to try to reduce unnecessary workload in schools (DfE, 2017c).

Workload is however only one aspect of the working conditions which influence teachers’ decisions about whether to remain in the profession. For years, researchers using administrative datasets found that pupil characteristics, particularly the deprivation of a school’s intake, were the best predictor of high teacher turnover in schools (Boyd et al., 2005; Hanushek et al., 2004; Scafidi et al., 200 7 ; Allen et al., 2018). However, following pioneering research by Eileen Weiss (1999) and Richard Ingersoll (2001), a new wave of research utilising survey data has demonstrated that the association between pupil deprivation and teacher retention is largely eliminated when measures of working conditions are included in the models (Simon & Johnson, 2015). The best articles in this literature utilise linked survey and administrative data and use factor analysis to identify latent variables measuring working conditions in schools (Boyd et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2012 ; Ladd 2011). These studies generally find that the social aspects of school life, such as leadership/management and staff collaboration, are the best predictors of teacher retention (Simon & Johnson, 2015). Interestingly, two studies which analyse experienced teachers and early-career teachers separately found that working conditions have a stronger influence on the retention of those that have recently qualified (Boyd et al ., 2011; Kukla- Acavedo, 20 09 ), making working conditions a candidate for explaining the recent decline in early career retention. Since 2015, two important extensions have been made to this literature. First, Kraft et al. (2016) have conducted the first analysis of working conditions using school panel data, allowing them to get closer to a causal analysis. Echoing previous research, they find that the nature of leadership and teacher relationships are strongly associated with retention. The robust relationship between leadership/management and retention across this literature begs questions about which specific leadership practices matter most. The second development in the literature has begun to address this question. Bloom et al. (2015) use data from the World Management Survey, which measures the use of evidence-based management practices in 1,800 schools across eight countries. Although they study pupil attainment as their outcome, their findings are largely consistent with those from the education literature in that “people management” practices - such as rewarding high performers and managing talent - are the strongest predictors of school performance. Fryer (2017) reports on a field trial in which school principals were given intensive training in a related set of practices – including teacher observation and coaching – and find a positive causal effect on attainment. The latest studies on

working conditions therefore suggest that working conditions really matter, both for teachers and their pupils.

In Chapter 2 of this thesis, I take a detailed look at entry into the teaching profession. Existing research in this area tends to be limited to interviews or surveys with either in-service teachers or trainees (Matthias, 2014 ; Richardson et al., 2006; Roness & Smith, 2009; Roness & Smith, 2010 ; Sinclair, 2008; Watt & Richardson, 2007; Watt et al., 20 12 ). Research using objective measures and following cohorts from education into the labour market is comparatively rare, perhaps because of the demanding data requirements for conducting such a study. I am aware of only four papers that conduct such an analysis for teachers (Bacolod, 2007b; Chevalier et al., 2007 ; Goldhaber & Liu, 2003; Reback, 2004 ). All four use graduate cohort surveys, which have the advantage of following individuals into the labour market, allowing a comparison of the characteristics of those who do and do not choose to become teachers. However graduate cohort datasets are also limited by the narrow set of variables that they tend to include. In particular, they do not include a range of variables such as personality type, self-efficacy, social networks, and values which have been shown to predict occupational choice (Bentolila et al., 2010; Borghans et al., 2008; Cobb-Clark & Tan, 2010; Filer, 1986 ; Krueger & Schkade, 2008; Lyons et al., 2006 ; Nieken & Stormer, 2010; Quimby & Santis, 2006 ). Chapter 2 provides new evidence on this by analysing rich data on entry to the teaching profession in the UK stretching back to 1938. It begins by documenting a number of new descriptive findings: the proportion of ethnic minority teachers has risen with each new generation of entrants, but the conditional odds of somebody from an ethnic minority entering the profession have fallen substantially over the same period; the proportion of teachers whose parents also taught has steadily increased across four generations; and the well-known twentieth century trend towards a less female, more graduate workforce has levelled off among the most recent generation of teachers. I also model entry to the profession and show for the first time that personality type, particularly openness to new experience, is a very strong predictor of entry to the teaching profession. Using these models, I am able to identify groups of people who are up to four times more likely to enter the teaching profession than the average graduate. The findings of this study can be used to target future teacher recruitment efforts. In Chapter 3, I return to the issue of working conditions. The existing research using survey data to model teacher retention is limited by the breadth of the questionnaires used to measure working conditions, which often contain around 20 questions (Boyd et al., 2011 ; Ladd, 2011; Johnson et al. 2012; Kraft et al., 2016). Moreover, the data they use in these studies covers only a single US state in each case. I extend this literature by modelling teacher job satisfaction and desire to move school

participants’ original school. This research represents some of the first credible findings that subject- specific CPD has a positive causal impact on teacher retention.

Teacher shortages are prevalent in public school systems around the world (Dolton, 2006). In the thirty-three countries and regions included in the main report on the Teaching and Learning International Survey 2013, over a third of teachers work in schools in which the head teacher reported significant difficulties with recruitment (OECD, 2014). Indeed, staff shortages were on average cited by head teachers as the most important constraint on good quality teaching. In recent years, demographic trends and policy changes have contributed to an increase in the severity of these shortages in many countries, prompting organisations including the UN, World Bank, OECD and the EU to warn that recruitment efforts need to be stepped up (Figazzolo, 2012; World Bank, 2013; Schleicher, 2011 ; Ranguelov et al., 2012 ). In England, the context for this study, shortages are also a growing problem. The Department for Education (DfE) uses its Teacher Supply Model to estimate the number of teachers required in the English school system each year. On the supply side, the model takes into account all flows into and out of the profession, which vary depending on the state of the economy and the age profile of the teaching workforce, among other factors. On the demand side, the model takes into account the number of pupils of school age, determinants of which include the number of births and net migration patterns. The difference between these two numbers can then be used to calculate the number of teachers who need to be recruited each year in order to balance supply and need, within current class size limits. As the pupil population has begun to grow in recent years however, the DfE has been missing these recruitment targets by increasing amounts: 1% in 2012/13, 5% in 2013/2014 and 9% in 2014/2015 (NAO, 2016). School leaders tend to respond to teacher shortages by either lowering recruitment standards, increasing use of temporary teachers or increasing class sizes (Smithers & Robinson, 2000), all of which have been linked with reduced pupil attainment (Fredriksson et al., 2012; Mocetti, 2012; Schanzenbach, 2006). There is also some evidence to suggest that pupils from poorer families are most likely to suffer from such sub-optimal staffing arrangements (Allen & Sims, 2018 a; Clotfelter et al., 2006 ). Governments have responded to these shortages with policies designed to attract and retain teachers. In England, for example, the Department for Education currently spends £167m per year on bursaries to try and incentivise people to train as teachers and a further £16.6m on marketing campaigns (NAO, 2016). However, a lack of knowledge about which types of people have the highest propensity to enter teaching (Goldhaber et al., 2014 a) has hampered policymakers’ efforts to target such policies.