Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

The sociological perspective on gender relations, emphasizing that biological facts do not determine specific forms of social relations between men and women. It discusses the enormous variation in gender relations throughout history and the factors contributing to their transformation. The text also touches upon the progress women have made in terms of formal rights, earnings, and social attitudes towards homosexuality.

Typology: Lecture notes

1 / 40

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

Final Draft, August 2009

The transformation of gender relations since the beginning of the 20th^ century is one of the most rapid, profound social changes in human history. For the more than 7,000 years of human history since settled agriculture and early states emerged, male domination has characterized the gender relations of these societies and their successors. Even at the beginning of the 20 th^ century, men and women were generally viewed as occupying sharply different roles in society: a woman’s place was in the home as wife and mother; the man’s place was in the public sphere. Men had legal powers over the lives of their wives and children, and while wife beating was never strictly legal in the United States, its practical legal status was ambiguous and perpetrators of domestic violence rarely punished. To be sure, articulate critics of patriarchy – rule by men over women and children – had emerged by the end of the 18th^ century, and the movement for the right of women to vote was well under way by the end of the 19th^ century, but nevertheless, at the beginning of the 20 th^ century the legitimacy of patriarchy was taken for granted by most people and backed by religious doctrines that saw these relations as ordained by God.

By the 21st^ century only a small minority of people still holds to the view that women should be subordinated to men. While all sorts of gender inequalities continue to exist, and some of these seem resistant to change, they exist in a completely different context of cultural norms, political and social rights, and institutionalized rules. Male domination has not disappeared, but it is on the defensive and its foundations are crumbling.

In this chapter we will explore the realities of gender relations in the United States at the beginning of the 21st^ century. We will begin by defining the concept of “gender” in sociological terms and explain what it means to talk about gender inequality and the transformation of gender relations. This will be followed by a broad empirical description of the transformations of gender in America since the middle of the 20th^ century, and an explanation of those transformations. This will provide us with an opportunity to explore a central general sociological idea in discussions of social change: how social change is the result of the interplay of unintended changes in the social conditions which people face and conscious, collective struggles to change those conditions. The chapter will conclude with a discussion of the dilemmas rooted in gender relations in the world today and what sorts of additional changes are needed to move us closer to full gender equality.

I. G ENDER, NATURE AND THE PROBLEM OF POSSIBLE VARIATION

At the core of the sociological analysis of gender is the distinction between biological sex and gender: sex is a property of the biological characteristics of an organism; gender is socially constructed, socially created. This is a powerful and totally revolutionary idea: we have the potential capacity to change the social relations in which we live, including the social relations between biologically defined men and women. Sometimes in the media one hears a discussion in which someone talks about the gender of a dog. In the

sociological use of the term, dogs don’t have gender; only people living within socially constructed relations are gendered. 1

This distinction raises a fundamental question in sociological theory about what it means to say that something is “natural”. Gender relations are generally experienced as “natural” rather than as something created by cultural and social processes. Throughout most of history for most people the roles performed by men and women seem to be derived from inherent biological properties. After all, it is a biological fact that women get pregnant and give birth to babies and have the capacities to breastfeed them. Men cannot do this. It is biological fact that all women know that they are the mothers of the babies they bear, whereas men know that they are the fathers of particular children only when they have confidence that they know the sexual behavior of the mother. It is a small step from these biological facts to the view that it is also a fact of nature that women are best suited to have primary responsibility for rearing children as well, and because of this they should be responsible for other domestic chores.

The central thesis of sociological accounts of gender relations is that these biological facts by themselves do not determine the specific form that social relations between men and women take. This does not imply, however, an even stronger view, that gender relations have nothing to do with biology. Gender relations are the result of the way social processes act on a specific biological categories and form social relations between them. One way of thinking about this is with a metaphor of production: biological differences rooted in sex constitute the raw materials which, through a specific process of social production, get transformed into the social relations we call “gender”.

Now, this way of thinking about sex and gender leaves entirely open the very difficult question of what range of variation in gender relations is stably possible. This is a critical question if one holds to a broadly egalitarian conception of social justice and fairness. From an egalitarian point of view, gender relations are fair if, within those relations, males and females have equal power and equal autonomy. This is what could be termed “egalitarian gender relations.” This does not imply that all men and all women do exactly the same things, but it does mean that gender relations do not generate unequal opportunities and choices for men and women.

The sociological problem, then, is whether or not a society within which deeply egalitarian gender relations predominate is possible. We know from anthropological research that in human history taken as a whole there is enormous variation in the character of social relations between men and women. In some societies at some points in history, women were virtually the slaves of men, completely disempowered and vulnerable. In some contemporary societies they must cover their faces in public and cannot appear outside of the home without being accompanied by an appropriate man. In

(^1) There are peculiar circumstances in which animals could be said to have a socially constructed gender. In

the spring of 2009 a female horse, Rachel Alexandra, won the Preakness stakes, one of the premier horse races in the United States. This horse was the first filly in 85 years to win this race. News headlines about the race included things like the MSNBC website banner “You go, girl! Filly wins Preakness Stakes thriller.” Commentators before the race talked about Rachel Alexandra being able to “run with the boys.” Since cultural representations are one of the aspects of “constructing” gender relations, this is an instance in which an animal’s sex is being culturally represented as gender.

aggressive than women and, on average, have stronger instinctual proclivities to dominate, and that woman because of genes and hormones are on average more nurturant and have stronger dispositions to engage in caregiving activities. However, regardless of what are the “natural” dispositions of the average man and woman, it is also equally certain that there is a tremendous overlap in the distribution of these attributes among men and among women. There are many women more aggressive than the average male and many men more nurturant than the average female. It is also virtually certain that whatever are the behavioral differences between genders that are generated by genes and hormones, society and culture exaggerate these differences because of the impact of socialization and social norms on behavior. You thus cannot take the simple empirical observation of the existing differences in distributions of these traits between genders and infer anything about what is the “true” biological difference under alternative conditions.

This general point about the relationship between the distribution of underlying biological dispositions in men and women and the distribution of manifest behaviors of men and women under existing social relations is illustrated graphically in Figure 15.1. This figure illustrates the distribution of time spent taking care of babies and young children by mothers and by fathers in two-parent households under two hypothetical conditions: The top graph represents this distribution in a society like the United States in which there are strong cultural norms which affirm that taking care of infants is more the responsibility of mothers than of fathers. The bottom graph represents the hypothetical distribution of such behaviors in a society in which the norms say that it is equally good for fathers as for mothers to take care of infants. In the first case girls are socialized to believe that they should take care of babies and the prevailing norms are critical of mothers who hand off that responsibility to others. In the second case both boys and girls are taught that it is good thing for both fathers and mothers to do intensive caregiving and the prevailing norms create no pressures for mothers to take on this responsibility more than fathers.

In this second, hypothetical world it could still be the case that mothers on average do spend more time in infant care. Even if there was no cultural pressure on them to do so, the underlying biologically-rooted dispositions could lead, on average, to some gender division of time spent on this task. We do not know how big the gender gap in caregiving of infants would be because it is not possible to do the experiment. But what we know virtually for certain is that the gap would be smaller than it is in the world in which we live today.

These observations on gender, nature, and the possibilities of much more egalitarian relations than currently exist constitute the theoretical background for the rest of this chapter in which we describe the empirical changes that have occurred in recent decades and explore the conditions which would make further changes towards gender equality possible in the future.

What follows below is a brief descriptive tour through some of the major changes in patterns of gender inequality during the last decades of the twentieth century. The simple story is that there have been tremendous gains in the direction of greater equality, but significant inequalities remain.

It is hard for most people alive today to really understand how it could be that before 1920 women in the United States did not have the right to vote. This was justified on many grounds: they were not as rational or intelligent as men; they were not really autonomous and would have their votes controlled by the men in their lives; like children, they were ruled by their emotions. The result is that women were not really full political citizens until the third decade of the 20th^ century. Even then, it would be many decades more before they had the same social and economic rights as men. Until the 1930s, married women were not allowed to travel on their own passports; they had to use their husbands. Until World War II, formal and informal “marriages bars” were in place in many parts of the United States, prohibiting married women from many clerical jobs and public school teaching. One historian described the logic of marriage bars for teachers this way: “Prejudice against married women as teachers derived from two deeply rooted ideas in American society: first, that women’s labor belongs to their husbands, and second, that public employment is akin to charity. School authorities doubted that women could service their families and the schools without slighting the latter.”^2 It was not until the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 that discrimination against women in jobs, pay, and promotion was made illegal. Even though in the 1970s a Constitutional Amendment to guarantee equal rights for women – the Equal Rights Amendment – failed to pass the required number of states, by the end of the 20th^ century, virtually all of the legal rules which differentiate the right of men and women had been eliminated. Aside from a few isolated contexts in which women are barred from certain activities – for example, direct combat roles in the military – women now do, effectively, have equal formal rights to men.

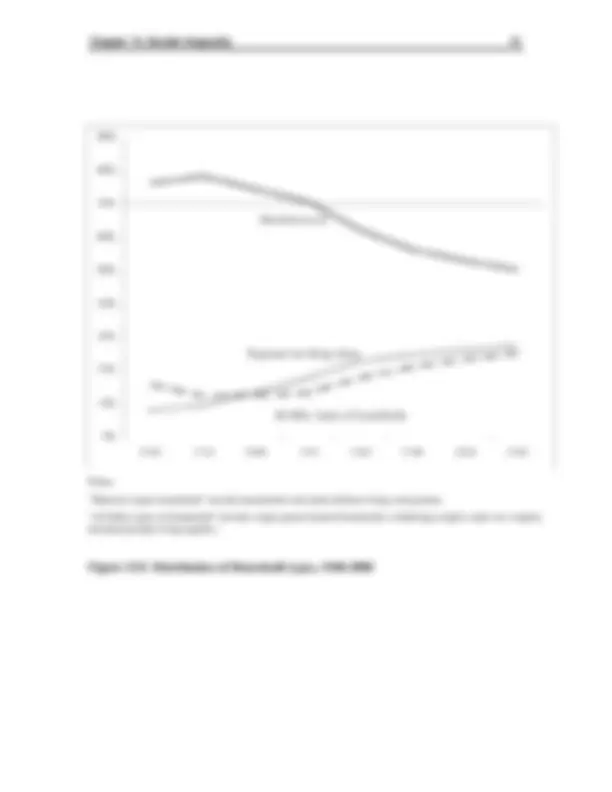

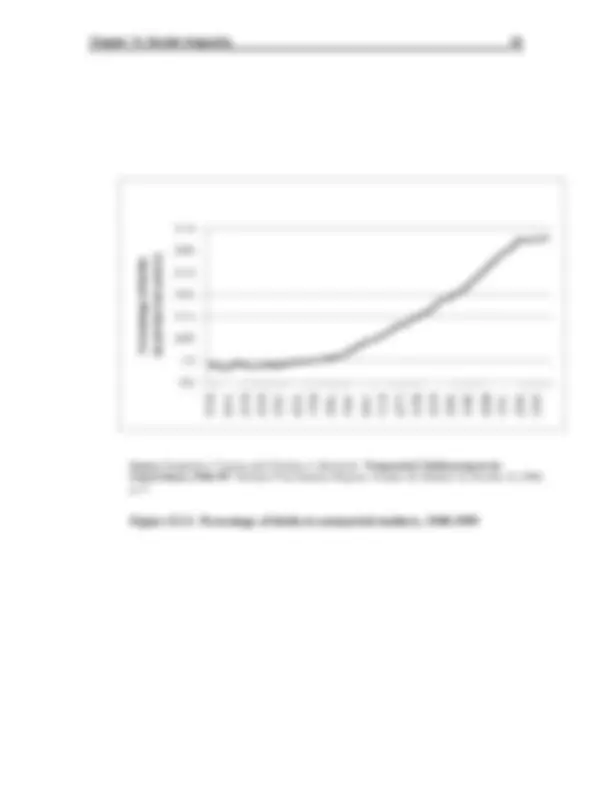

In 1950 only about 10% of married women with children under 6 were in the paid labor force; 90% were stay-at-home Moms (Figure 15.2) Even when the youngest child reached school age, at the mid-point of the twentieth century over 70% of married women were still full time homemarkers. This was clearly the cultural standard, at least for white women. For black women the norm was always weaker, although it was still the case in 1950 that 64% of black women with children over 6 did not work in the formal paid labor force.

-- Figure 15.2 about here -- By the beginning of the 21st^ century the situation had dramatically changed: Over 60% of mothers with children under six and nearly 80% of mothers with children in

(^2) Eric Arnesen, Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-class History (CRC Press, 2006), p. 1359

Much of this gender gap in pay (after statistical controls) reflects the large differences in pay that continue to exist for jobs that are identified with women compared jobs associated with men: parking attendants typically earn more than pre-school teachers, for example. It is a difficult task to sort out exactly why such stereotypically female jobs generally earn less than stereotypically male jobs. Some of this may be due to what economists call “overcrowding”: if women are highly-concentrated in certain jobs, either through discrimination or self-selection, then there will tend to be an oversupply of people competing for such positions, and thus the wages will be bid down. In this view, the lower pay for women simply reflects the supply-and-demand dynamics of markets. Many sociologists, in contrast, argue that wages are shaped by cultural expectations and norms, but simply by the supply and demand conditions of markets. Jobs that are associated with women are traditionally devalued, and the kinds of skills those jobs require deemed less valuable than the kinds of skills associated with male jobs. More specifically, skills connected to caregiving and nurturance are undervalued in markets. Much of the gender gap in pay between male and female jobs is linked to these cultural standards.

Gender inequality in the extent to which women occupy positions which confer significant power is more difficult to assess than inequality in pay or in occupational distributions. One indicator is presence of women on boards of directors and top managerial positions in large corporations. In 2008, 15.2% of the seats on boards of directors in Fortune 500 firms were held by women, 15.7% of the corporate officers in those firms were women, and 3% of the CEOs were women (Figure 15.6). These figures certainly show a significant under-representation of women, but they also mark a significant improvement over the past. What is more difficult to ascertain is the extent to which the under-representation reflects systematic barriers and discrimination faced by women today. At least some of this under-representation of women at the top of managerial hierarchies is simply the historical legacy of the virtual absence of women from lower levels of the management structure 25 years ago, since women need to be in the pipeline of promotions to make it to the top by the end of their careers. How much of the rest of the under-representation is the result of gender-specific barriers and discrimination faced by women – especially the strong barriers referred to as the “glass ceiling” – and how much of it reflects the ways in which women themselves may choose not to compete in those hierarchies because of their personal priorities is an extremely difficult empirical question. It is particularly difficult because, of course, the choices women make may themselves be conditioned by the experience of barriers: the barriers make managerial careers for women more difficult, and by virtue of this they may decide it isn’t worth the fight and thus they “select themselves” out of the competition.

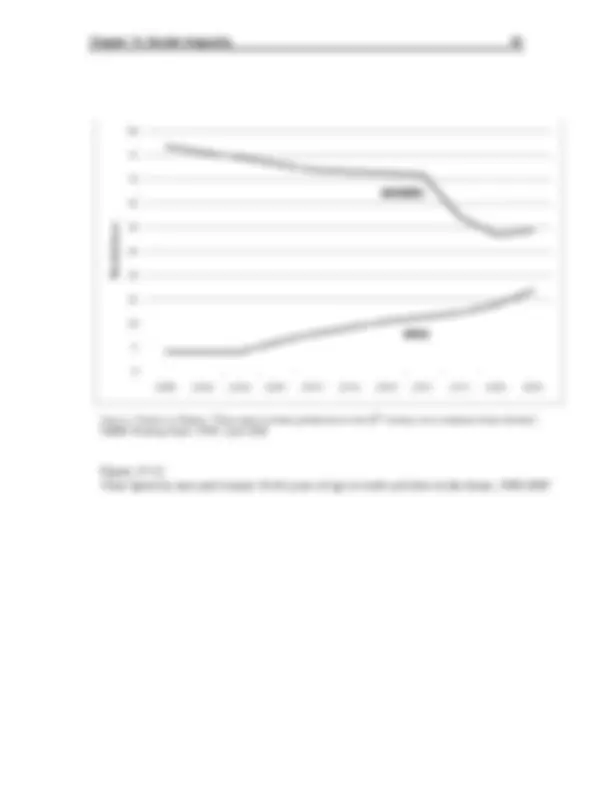

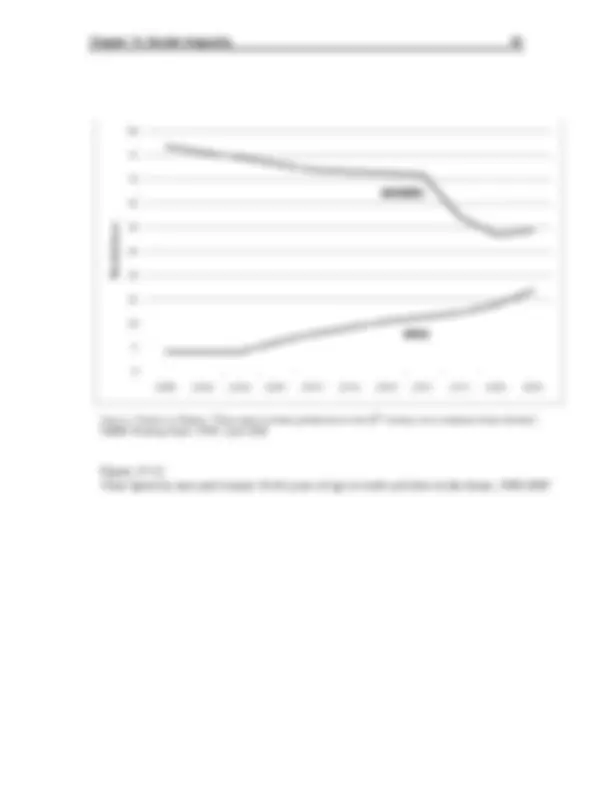

-- Figure 15.6 -- What about women in positions of political power? Figure 15.7 presents the percentage of elected officials in the U.S. Congress, State Legislatures and Statewide elective offices. In 1979, only 3% of people in the US Congress were women, and only around 10% of people elected at the state level were women. By 2009 women constituted nearly a quarter of all people elected at the state level and just under 17% of people in Congress. This is certainly progress, but it still puts the United States well below most

other economically developed democracies. As indicated in Table 15.2, the United States ranks 20 th^ among developed democracies in the proportion of women in the national legislature. Sweden is first with 47%. Other Northern European countries are all above 30%. Even among the English speaking countries, which are generally lower than other European countries, only Ireland has fewer women in the national legislatures than does the United States.

-- Figure 15.7 --

The period since the end of the WWII has also witnessed a dramatic and rapid change in the nature of family structure and the composition of households.

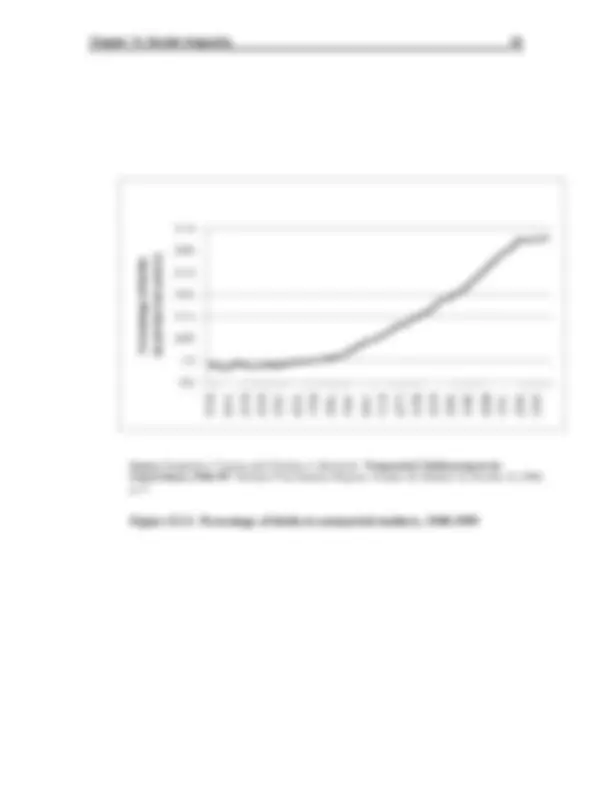

At midcentury almost 80% of all people lived in households in which there was a married couple. This meant that many adult children lived with their parents until getting married, or only lived on their own for a very short period. This was clearly the cultural standard. Other household forms were either deviant or transitional. By 2008 only half of all households consisted of a married couple. Households of a single person living alone increased from under 10% of all households in 1940 to almost 30% in 2009. The remaining households consisted of cohabiting unmarried couples (including same-sex couples), households headed by a single parent and households of single people with roommates (Figure 15.8). In the half century following the end of WWII the single, monolithic cultural model of household composition had largely disappeared and been replaced by a much more heterogeneous array of forms.

-- Figure 15.8 about here -- These changes in the distribution of types of households reflect important changes in family structures and marriage patterns over the same period. In the last half of the twentieth century in a variety of ways, marriage has become a less central and stable institution in many people’s lives. In 1960, only 7% of women aged 30-34 had never married. By 2007 this had increased to over 27% (Figure 15.9.) For those who choose to marry, marriages have become much less durable: In the early 1950s, people who go married had only about a 12% probability of getting divorced within ten years. By the early 1980s this figure was nearly 30% (Figure 15.10). This very high rate of divorce for marriages in the 1970s and 80s meant that demographers estimate that eventually somewhere between 45-50% of these marriages will end in divorce.^3 Along with this decline in marriage, an increasing number of children are born to single mothers.

(^3) Lynne Casper and Suzanne Bianchi, Continuity and Change in the American Family (Thousand Oaks:

Sage, 2002), p.25. While it is easy to count the number of divorces in any given year, it is much more difficult matter to estimate the proportion of marriages that eventually end in divorce, since for a given cohort of marriages this percentage constantly increases over time until everyone in the cohort has died. The estimate of the percentage of marriages that end in divorce is therefore a projection into the future based on trends to the present. It is possible, however, to make broad comparisons across cohorts, such as the following: “14% of white women who married in the 1940s eventually divorced. A single generation later, almost 50 percent of those that married in the late sixties and early seventies have already divorced [by the early 1990s].” Amara Bachu, Fertility of American Women: June 1994 (Washington D.C.: Bureau of the Census, September 1995), xix, Table K. (Cited on page 5 of The Abolition of Marriage, by Maggie Gallagher).

began to change rapidly in the decades after 1950 through increases in the labor force participation rates of married women, and increasingly changes in their occupational roles and relative earnings. Initially these changes in the public roles of women were not reflected in significant change within the division of labor in the home. As shown in Figures 15.13 between 1965 and 1975 men hardly increased their involvement in housework labor at all, while women decreased theirs quite a bit. The initial affect of increased labor force participation of wives and mothers was messier houses! But then, between 1975 and 1985 men did gradually begin to do more. This is especially dramatic for ordinary housework. In 1965 mothers spent 23 times more time cleaning house than did fathers. This declined to only 13.5 times more in 1975, but this was entirely because mothers on average decreased the amount of time they spent cleaning house from an average of around 19 hours a week to just over 12 hours a week. In both periods fathers typically spent less than 1 hour a week on routine housecleaning. By 2005 the ratio had declined to 4.3:1, but this time much of the change came from a doubling of fathers’ housecleaning labor. This is still far from an equal sharing of housework, but it reflects some real movement in that direction. Full-time working mothers still do a second shift at home, and they have less free time than their husbands, but the disparity has begin to decline.

-- Figures 15.12 and 15.13 about here

Sexuality has an extremely complex relation to gender relations in general and gender inequality in particular. Some scholars have argued that one of the central motives historically for male domination centered on the problem of female fertility: the only way that men could guarantee that they were in fact the fathers of their children was to control the bodies of the women who were to be mothers of those children. Controlling female sexuality and fertility was therefore a central component of the social processes that generate male domination. The continuing controversies in American society over the availability of certain forms of contraception and, above all, abortion, reflect this age-old issue of the social processes through which biological reproduction are controled.

Sexuality is also tied to inequality in gender relations through sexual violence. Sexual violence both outside of marriage and inside of marriage is a central feature of male domination in many societies, including the contemporary United States. It both expresses the unequal power relations between men and women and helps to reinforce that inequality, as the greater vulnerability of women to such violence inhibits their easy movement in public spaces.

Social attitudes and treatment of homosexuality are also bound up with gender relations in so far as men and women having sexual relations with members of their own sex violates one of the core elements of the social norms regulating male/female relations. Certainly the idea of same-sex marriage is seen by many people as a direct threat to a conventional understanding of how families should be structured around traditional, inegalitarian forms of gender roles.

As is the case for the other trends we have discussed, the transformation of social norms and legal rules around sexuality has been dramatic since the middle of the 20th century. Part of this is anchored in technological changes, especially the invention and

widespread dissemination of the birth control pill, which made the control by women of their own fertility much easier and reliable and opened the door – some people believe – for the “sexual revolution”. Equally important were changes in laws around availability of birth control and the fairly rapid change in social norms about their visibility and accessibility. Even in the case of the most contentious aspect of control over female fertility – abortion – a majority of people in the United States believe that women should have the right to abortion. In 2009, only around 20-25% of people believe that abortion should be illegal in all cases, and a clear majority believes it should be legal in most or all cases.^5

The transformations in sexual norms, however, go far beyond simply the issues of birth control. Sexual violence and sexual abuse have become much more heavily condemned and controlled since the middle of the twentieth century. Until the mid-1970s rape was a defined as a crime only if the perpetrator was not a spouse. By the first decade of the 21st^ century half of the states in the United States had completely removed the marital exemption from rape laws, and the remaining states treated it as a crime, but of lesser severity than rape outside of marriage. Sexual abuse of children has also become a much more salient issue, particularly in the aftermath of the repeated scandals of abuse of children by priests. Sexual harassment in workplaces, schools, and other public places, which once was regarded by many men as at worst coarse behavior, is now acknowledged as a form of serious intimidation of women that generates real harms.

Perhaps the most dramatic transformation of sexual norms concerns homosexuality. After all, sexual violence and abuse of children were always thought of as reprehensible; what has changed is the visible public attention these are given. In the case of homosexuality the prevailing attitudes, norms and the laws have changed in fundamental ways. In the 1950s homosexuality was a criminal offense in all states in the United States under the rubric “sodomy laws,” even if the statutes were only erratically enforced. There were periodic police raids on gay bars and being revealed as a homosexual was grounds for loosing a job. Homosexuality was broadly regarded as immoral and shameful, and most homosexuals had to remain “in the closet” to avoid stigma and ostracism.

In 1961 Illinois became the first state to repeal its sodomy Law. By 2003 such laws had been repealed in throughout most of the United States except for Southern States and a few others. In 2003 the Supreme Court ruled that such laws were unconstitutional and that the state cannot restrict the right of adults to engage in consensual sexual activity.

By the beginning of the 21st^ century, laws criminalizing homosexuality had been ruled unconstitutional and the public acceptance of homosexuality as simply a variation on human sexuality had become fairly widespread. Discrimination in employment and housing against homosexuals is broadly viewed as illegitimate, and as of 2009 in many states it is illegal under anti-discrimination statutes. Even in the military, homosexuality was tacitly accepted under the awkward “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy adopted in the Clinton Administration, and it is very likely that by the second decade of the century formal restrictions on homosexuality in the military will be dropped. On the most high

(^5) Gallup Poll, May, 2009; Quinnipiac University Poll, April 2009; Roper Public Affairs and Media poll,

May 2009.

The problem of the interests of men^6

Inequalities of power and privilege do not continue out of sheer momentum; they require considerable social energy and resources to be reproduced. If, over time, the interests of powerful people become less tied to a particular form of oppression, they are likely to devote less energy and fewer resources to sustain that inequality, and this makes the oppression in question more vulnerable to challenge. In the case of gender inequality, the interests of men in general, and elite, powerful men in particular, in maintaining certain aspects of male domination and gender inequality weakened over time. This doesn’t mean that men ceased to be sexist. They have all sorts of attitudes and beliefs which impeded – and continue to impede – gender inequality. The key idea here is that many men also had interests which weakened their stake in male domination.

A good example of this is the economic interests of employers in capitalist firms, particularly once their need for highly educated, literate labor increases. Increasingly in the period after the Second World War, because of technological change and the growth in importance of the service sector in the economy, employers needed to find a new source of educated labor for white collar jobs. Women were an obvious potential largely untapped source of such labor. But to get women into the labor force it was necessary to ease the barriers to their participation. Once in the labor force, employers had interests in promoting talented employees, giving them more responsibilities, and so on. Now, employers were also overwhelmingly men and generally had sexist attitudes, and this continued to interfere with the most efficient hiring and promoting practices, particularly when sexism also allowed them to pay women less than men. For these reasons, male employers were rarely at the forefront of actively challenging sexism. Nevertheless, their interests in profit-maximizing of their capitalist firms and their interests as men in maintaining traditional gender relations often cut in opposite directions. This increasing incoherence of their interests undermined their determination to defend sexist practices when those practices came under challenge. Robert Jackson states this explanation for the erosion of women’s subordination this way: “The driving force behind this transformation has been the migration of economic and political power outside the household and its reorganization around business and political interests detached from gender….Gender inequality declined because modern society transferred social power from people committed to preserving men’s advantages to institutions and people whose interests were indifferent to gender distinctions....While prejudices against women still ruled many actions of men with power, their institutional interests repeatedly prompted them to take actions incompatible with preserving gender inequality .” 7

The crisis of female domesticity

Changes in the interests of men within the public sphere are only part of the story. There is also a second powerful cluster of processes at work in the radical transformation of gender relations: processes which have eroded the stability of the traditional role for women in the private sphere and therefore affect the interests of women with respect to

(^6) The argument presented here concerning the importance of the weakening of coherent interests among

men in male domination comes from the work of Robert M. Jackson, Destined for Equality: The Inevitable Rise of Women’s Status (Harvard University Press, 1998) (^7) Jackson, Destined for Equality , p.2. italics added

gender relations. These processes have been described by Kathleen Gerson as generating a crisis of female domesticity in the United States.^8

The American family in the 1950s can be seen as embedded in a systematic structure of interconnected, reinforcing social supports for female domesticity. There are five main elements in this system:

This was a real system, a coherent, interconnecting set of social forces that reinforced each other and sustained the pattern of gender relations in which women were very

(^8) Kathleen Gerson, Hard Choices (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986)

be known as the “women’s movement” was essential form this. The struggles took many forms: Court cases against specific forms of discrimination against women were brought by individuals and organizations. Women’s political organizations were established to lobby for legislative change and play an active role in shaping political agendas. The Democratic Party took on equal rights for women as a central policy objective, even if there was uneven enthusiasm for actively pursuing this agenda. Women’s caucuses and networks were formed within professional organizations and academic disciplines to pressure for changes in internal policies and priorities. Women’s Studies programs were established in Universities and there was a proliferation of serious academic journals focused on gender. Sexist language and practices were challenged in public meetings and institutional practices. At times there were significant public protest demonstrations, but more often the challenges took the form of arguments within meetings where institutional decisions were made.

The trajectory of these challenges was by no means smooth. There were major defeats, such as the failure of the Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Frequently the demands of women were mocked, and feminism as the articulated way of talking about gender relations and male domination, was often caricatured and denounced. Nevertheless, the cumulative effect of these challenges over time has been to fundamentally shift the terms of public discussion over gender. Overt defenders of male domination are on the margins of the public debate with virtually no chance of rolling back the major institutional and legal changes that have occurred. There is also virtually no chance that the major social structural changes around gender inequality will be substantially reversed. The United States is unlikely ever to return to a social pattern of high fertility and large families, with a predominance of stable life-time marriages in which most married women were full-time housewives and women no longer aspired to challenging careers in the public sphere. The issue now is how much further can we go in eliminating the remaining forms of gender inequality, not whether a regime of unequivocal male domination can be reinstated.

IV. PROSPECTS FOR FURTHER TRANSFORMATION: REMAINING CRITICAL TASKS

In the United States at the beginning of the 21 st^ century, men and women both have complex and sometimes contradictory interests with respect to the problem of pushing forward the frontiers of gender equality. While most women benefit from greater gender equality, there are certainly some women who experience increasing equality as a threat, as imposing costs on them since this would further erode the historic protections of women that accompanied their economic dependency on men. For women who, for whatever reasons, embrace the ideal of life-long female domesticity and really want to be fulltime housewives and mothers, the decline of this cultural ideal and the accompanying social supports for such a life is harmful.

The ways in which many men have something to lose from further advances in gender equality are pretty obvious. There are certainly privileges for men that accompany gender inequality, privileges in the workplace and at home, that are undermined by gender equality: the removal of obstacles to women entering professions and managerial positions means that competition for these jobs increases. Some men, undoubtedly, would have gotten better jobs if women dropped out of the race. If there were true pay equity in the wage structure of jobs, the wages of some men would certainly decline. Because of

resource constraints, gender equality in the funding of sports at universities means a reduction in funding for some traditionally male sports. At many universities some inter- collegiate men’s sports had to be dropped altogether. And if gender equality within the division of labor in the home were to increase to the point that men shared equally in the time-consuming burdens of domestic tasks, then the leisure time of many married men would decline. But it is also true – and this is a really important point that is often neglected – that in certain important ways men potentially have much to gain from deeper and more robust forms of gender equality in American life. In a world of real gender equality men would have a richer array of life choices around parenting and work. The dominant models of masculinity make it difficult for many men to play a full and active role in caregiving activities within the family. It is very difficult for men to interrupt their careers to take care of small children. The dominant models of masculinity also promote intense forms of competitiveness that make many men miserable, working excessively long hours, losing site of more important things in their lives. Further advances towards gender equality will potentially involve a significant restructuring of the rules that govern the relationship between work and family, and this would give both men and women greater flexibility and balance in their lives. So, while men do have things to lose from a full realization of the ideal of gender equality, they also have potentially important gains.

In order to move more fully in the direction of gender equality, perhaps the key problem that needs to be solved is transforming gender divisions of labor within the family.^9 As we have seen, even after the major changes that have occurred in the participation of women in the labor force, as we have seen it is still the case that women spend considerably more time doing domestic labor – housework and childcare – than do men. This is in and of itself a source of gender inequality insofar as it means that married men with children have more free time than their wives, at least if the wife also works full time in the labor force. While there is no inherent reason why spouses should do exactly the same things in the household, from the point of view of egalitarian conceptions of fairness they should share equally in the burdens of domestic responsibilities and this means that whatever is the division of labor they should end up with the same amount of free time. This is not the case in most families.

The inequalities in the gender division of labor, however, have an impact far beyond simply the specific problem of free time available to men and women within families. It also deeply affects inequalities in the labor market and employment. The greater domestic burdens that, on average, married women have compared to married men act as a significant constraint on the kinds of jobs they can seek in the labor market. It also affects the attitudes of all employers towards prospective women employees.

It is one thing to demonstrate that the gender division of labor within the family constitutes one of the central social processes that impede further advances towards gender equality, and another to do something about this. Public policy can directly intervene in public forms of gender inequality in all sorts of ways: legal rules against discrimination, changing in funding formulas for university programs, affirmative action,

(^9) For a wide ranging discussion of the linkage between the gender division of labor within the family and

the broader problem of gender inequality, see Janet Gornick and Marcia Meyers, Gender Equality: transforming family divisions of labor , volume VI in the Real Utopias Project (London and New York: Verso, 2009).

resources a person can bring into the family plays a role, and this is the aspect of the problem that can be affected by public policies over pay equity.

The second public policy that could have a significant impact on the gender division of labor within families concerns the availability of childcare services, including early infant daycare, preschool programs, and afterschool programs. A fully developed system of such services would include daycare facilities within workplaces, neighborhoods, and schools. In the absence of such services, the responsibility for providing caregiving to children falls entirely on the family, and in practice this generally means mainly on mothers. This undermines the kinds of jobs they can seek and the hours they can work, and makes it much more difficult to move towards an equal sharing of responsibilities within the family.

The final policy which would have a potentially important impact on the gender division of labor within the family is paid parental leaves for family caregiving responsibilities. These can be used at the birth of a child or for tending a sick family member. The United States shares with Australia the most limited legally required provisions for parental leave among all economically developed countries (see Figure 15.16). In the US there is no legal right for any paid family caregiving leave, and only two weeks of unpaid leave are required, and even this is only for businesses that employ over 50 workers. All other countries except for Australia have provisions for some degree of paid family caregiving leaves. In Sweden, for example, families are entitled to a total of 480 calendar days of paid child-based leave per couple. Of these 480 days, the first 390 are paid at 80% of the person’s salary, and the rest at 180 Swedish kroners per day ( which is about 18% of average wages). Mothers are also entitled to 14 weeks of paid maternity leave beginning seven weeks before birth. The 480 days of paid leave can be divided by mothers and fathers in whatever way they choose, except for a 60 day quota which is reserved for each parent. Naturally, as one would expect, the amount of leave taken by mothers is much greater than by fathers, but fathers have been slowly increasing the amount of leave they take.^10 Few other countries are as generous in their paid parental leave policies as Sweden, but every country (except Australia) provides at least some leave, and nearly all provide leave for fathers as well as mothers.

-- Figure 15.16 about here -- These kinds of requirements of paid family leave make it easier for families to juggle in a more balanced way the demands of paid work and family responsibilities. They do not, however, necessarily do much to change the gender division of labor within families, since when generous paid parental leaves are available, women are much more likely to take advantage of them than are men. Janet Gornick and Marcia Meyers have proposed a different format for these leaves which would encourage greater gender

(^10) This description of Swedish parental leave policy comes from : Rebecca Ray, Janet C. Gornick and John

Schmitt, “Who Cares? Assessing Generosity and Gender Equality in Parental Leave Policy Designs in 21 Countries” Center for Economic Policy Research , 2009

equality in their use^11. Instead of allocating, as in Sweden, the paid leaves to families , the leaves should be allocated to individual spouses on a “use it or lose it” basis. For example, in the Swedish case this would mean that mothers and fathers would each get allocated six and a half months of paid leave at 80% of pay at the birth or adoption of a child. Employers would be required to keep the seniority clock ticking while a leave was being taken so that men (and of course women too) would not feel that they were losing out in their career advancement while on leave. Over time with such individualized leaves it would be expected that men would begin to take leaves more extensively.

These three policies – pay equity, high quality publicly funded childcare, and paid parental leaves – would help to change the environment in which men and women grapple with the difficult issues of transforming gender relations. A skeptic of these kinds of policy proposals might argue that the cultural norms around appropriate roles for mothers and fathers are too deeply ingrained for these kinds of policies to have much of an impact. Unless they are highly coercive, men will simply not take much advantage of paid leaves, and while pay equity and good childcare might be desirable in their own right, they will have little impact on what happens inside of families because of the resistance of men. There are indications, however, that unmarried young men and women in the United States today are strongly disposed to more egalitarian relations. Kathleen Gerson, a sociologist at NYU, has done intensive research on how young men and women think about the way they want to live their lives when they form families. From her research she identifies three different ideal models of family relations held by the subjects of her research:

The participants in her study were then asked which of these ideals would be their first choice. For those who picked the “egalitarian model” as their ideal, they were also asked which would be their fallback position if they were unable to have their ideal. The results are extremely revealing about ideals and dilemmas at this point in the history of transformation of gender relations (see figure 15.17). There was very little gender difference in the stated ideals: over two thirds of both young men and young women in the study endorsed the egalitarian family model. The fallback positions of young men and women, however, were completely different: 73% of women who preferred the egalitarian family said that if this was not possible, they would prefer the self-reliant

(^11) See Janet Gornick and Marcia Meyers, Gender Equality: transforming family divisions of labor , volume

VI in the Real Utopias Project (London and New York: Verso, 2009).